Blue Economy in Bangladesh

Recommendations for social foundations and defining ecosystem boundaries

Updated at 31.08.2022

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subject

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subjectI. Introduction

The doughnut economic model sets out a framework to operate in the safe and just space where people’s needs are met and planetary limits are not exceeded (Raworth 2018). The challenge is to create economies that sustain social sustainability while at the same time safeguarding the live-giving systems of the Earth, including a protective ozone layer, fertile soils but also healthy ocean ecosystems(Raworth 2018). The oceans provide vital benefits and ecosystem services to humans. The health of societies is deeply intertwined with maritime ecosystems, as these provide a variety of ecosystem services including carbon sequestration, oxygen production, livelihoods and mental well-being. Proximity to coastal areas is also being associated with a better quality of life. At the same time, coastal communities face ocean- associated risks and are vulnerable to natural disasters intensifying through from climate change and as sea level rise (Nash et al. 2021).

Ocean environments are also threatened by various anthropogenic developments. Human population growth and technical advance increase the pressure on ocean health with rising demand for energy and seafood. The increasing industrialization of maritime areas causes further adverse effects of maritime pollution (Wan et al. 2018) and the destruction of natural infrastructure such as coral reefs and mangroves (Sutton-Grier et al. 2015). Increasing levels of green house gases in the atmosphere result in increasing ocean acidification, with severe consequences for maritime species and productivity (Guinotte et al. 2008). Last but not least, there are major geographical inequalities and disparities regarding these developments. It is anticipated that low income southern sea countries will suffer disproportionally from climate change impacts, that will likely have a greater impact in tropical regions affected by sea level rise (Cheung et al. 2009). One of these countries is Bangladesh.

II. Blue Economy in Bangladesh

Scope and issues of the maritime environment

Population rise coupled with rapid economic growth is putting extensive pressure on the environment and natural resources in Bangladesh (World Bank, UNDESA 2017). According to Jafrin et al, the country has to have a balanced socio- economic development in order to ensure optimum human well-being, and at the same time maintaining the balance in nature and ensuring sustainability for future generations (Jafrin et al. 2016). Following the recent international verdict on the maritime boundary disputes with the neighbouring countries Myanmar in 2012 and India in 2014 through the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, Bangladesh defines a huge ocean space under its jurisdiction (Hussain et al. 2019). The country now has exclusive rights to exploit and to explore maritime resources across an EEZ of 118.813 km2 (figure 1). This space is equivalent to 80% of the country’s total land mass of 147.570km2, and the country has prioritized it as a key source of future growth (Alam et al. 2021, Patil et al. 2019, Patil et al. 2018). Bangladesh is part of the Bengal Basin and the country’s land area is primarily dominated by the GBM Basin, which contains over 230 rivers and makes Bangladesh one of the largest deltas in the world (Patil et al. 2018). These rivers connect to a dynamic system of estuaries, islands and a coastal sea area (Barange et al. 2018)

Fig.1. Bangladesh's EEZ Source: Patil et al. 2018, p.20

Fig.1. Bangladesh's EEZ Source: Patil et al. 2018, p.20According to UNDESA, Bangladesh will see a rise in population size that is estimated to reach 193 million by 2050 (UNDESA 2019). Increasing population trends will likely also lead to expanding human activities and rising demands for maritime resources and ecosystem services.

The maritime environment of Bangladesh is one of the most productive global regions, sustaining the livelihoods of more than 35 million people that live within the country’s coastal region (Hussain et al. 2019).Human activities within this region include fishing, aquaculture, forest resources, nearshore transportation and agriculture. The fishing industry alone provides a substantial number of job opportunities and the domestic tourism industry has grown significantly along the coast in recent years. Next to this, areas of the Bay of Bengal within the country’s EEZ contain large untapped oil and gas reserves, and minerals of global economic value (Alam et al. 2021). Marine traffic is another growing sector, which already today accounts for 90% of all Bangladesh trade transports (Alam 2014).

Next to supporting the livelihoods of millions of people and providing opportunities and potential for economic development and the exploitation of resources, maritime environments of Bangladesh are already negatively impacted by economic activities and climate change. These include the uncontrolled and unplanned extraction of coastal and maritime resources as well as a rapid urbanization. Moreover, the country’s coastal inhabitants and ocean environments are exposed to extreme climate change impacts, including cyclones, storm surges, floods, sea-level rise and ocean acidification. Combined with manufactured hazards such as various forms of pollution, waterlogging and soil erosion, these stresses call for a sustainable approach to the management of the maritime areas of Bangladesh. An approach aimed at sustaining livelihoods, ocean health and national wellbeing (Sarker et al. 2019, Awal & islam 2019).

The concept of a blue economy promises a way of balancing economic activities in maritime areas without undermining the resilience and capacity of maritime ecosystems. The GoB has already embraced this concept to guide the rapidly changing use of ocean space and ensuring maximum economic benefits (Jafrin et al. 2016).

Introduction to Blue Economy

The concept of a blue economy promises a way of balancing economic activities in maritime areas without undermining the resilience and capacity of maritime ecosystems. The term “blue economy” emerged with prominence at the Rio+20 Summit of 2012, where countries discussed new ways of balancing out accelerating growth-trends in the ocean economy and the resulting decline of the ecosystems. After the Rio Summit, blue economy was widely used to describe policies promoting sustainable development of the ocean, in which economic growth does not reduce ocean health and in which conservation strategies contribute to poverty reduction. Such policies were commonly aimed at simultaneously enhancing the three dimensions of sustainable development: environmental, social and economic sustainability (Patil et al. 2019).

However, just like “green economy”, the metaphorical bigger brother of the blue economy, the concept remains contested. That relates to the underlying desire of knowing and measuring nature through economic terms, to think in profit potential of exploiting maritime resources, to generating revenue through activities of industries and other sectors in maritime environments, but also to loss and damages caused by natural or human-induced disasters. But, next to discourses resulting in a capitalization and accumulation of ocean environments, blue economy discourses may also shape policies and governance practices into pathways towards increasing sustainability (Silver et al. 2015).

In a study conducted at the Rio+20 Summit, Silver et al. localized competing discourses of the blue economy concept in global ocean governance. Among them, they identified (a) oceans as natural capital, and (b) oceans as small-scale fisheries livelihoods (Silver et al. 2015):

(a) oceans as natural capital

This discourse is centred on the challenging question of how to account and measure the economic value of oceans, and how to economically recognize natural infrastructures, such as mangroves or coral reefs, and important maritime ecosystem services, such as climate regulation (Silver et al. 2015). In this discourse, natural capital is debated as an ontological entity. Here, oceans are considered similar to business enterprises: Providing certain amounts of goods, services and value. Considering human-environmental relationships, people may invest in the oceans (e.g. through abstaining from harmful behaviour) and incidentally gain profit from investments (e.g. in the form of sustaining/creating ecosystem services). The following outcomes of this discurse are highlighted below, based on the study of Silver et al. (2015):

- Decision making within a blue economy must adequately account for nature and the value of ecosystem services

- Coastal and maritime diversity is important to sustain livelihoods

- Activities of a blue economy have to be based on people-centred biodiversity conservation

- There is a need to identify and closely observe maritime ecosystem services and to develop ways to account for their functioning, protection and restoration

Following this conceptualization of a blue economy, markets could provide mechanisms for climate change mitigation. Silver et al. particularly draw on one example from Rio +20, where participants at an event discussed the potential of blue carbon sequestration. Coastal ecosystems such as mangroves and salt marsh grasses take out CO2 from the atmosphere, which can be considered a valuable service. Additionally, fish may be viewed as a carbon-based unit commodity, rather than a resource only valuable for consumption (Silver et al. 2015).

(b) oceans as small-scale fisheries livelihoods

This discourse is centred on human-environment relations in terms of social sustainability, including poverty reduction and development as well as livelihoods and well-being of coastal communities. SSF are portrayed as embedded in these communities. Thus, a blue economy shall be concerned with meaningful social development of these communities. SSF are considered as providing food for the poor, employment for fishers as well as work and income for women. At Rio+20, crisis and degradation of SSF often was associated with policies supporting large-scale industrial fishing. Granting industrial fishing companies licenses without a good understanding of the social impacts the activities of large trawlers may have for coastal and maritime livelihoods was identified as an important issue. The following outcomes of this discourse are highlighted below, based on the study of Silver et al. (2015):

- SSF fishers should have rights to fish and to participate in fisheries management. Their concerns have to be carefully integrated in policies and have to be balanced against large-scale industrial fishing

- The rights demanded are broad and include the participation in decision-making processes, the recognition of knowledge and the territorial access to ocean spaces

- Regarding property rights, decisions may be made carefully and address issues of uncertainty, overcapacity and inefficiency.

To avoid negative social impacts of ocean privatization and industrial fishing activities, a human rights approach to fishing is advocated in the discourse of oceans as small scale livelihoods. This approach should consider: the secure access of SSF to fishing grounds; cultural values and collective benefits of SSF; and inclusive and participatory governance approaches in decision-making processes (Silver et al. 2015).

The discourses at the Rio+20 summit did not result in concrete definitions of a blue economy. Nevertheless, the ideas, principles and inputs for human-environmental relationships and economic developments of the oceans presented at the summit can be a starting point for defining how a truly sustainable blue growth strategy could be designed for Bangladesh. The country has maritime ecosystems extremely rich in biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, including the SoNG and the Sundarbans mangrove forest. The fisheries sector is also one of the fast growing blue economy sectors of Bangladesh (Chawdhury & Rokanuzzaman 2018) and the overall vast potential of the Bay of Bengal for national economic development is widely recognized in existing literature. Therefore, it is important to set and suggest guiding principles for blue growth developments in Bangladesh, and how maritime management can contribute to all three dimensions of social, economic and environmental sustainability.

III. From Blue Economy to Blue Doughnut Economy

Lieberknecht argues there is a fundamental disconnect between two dominating narratives concerning the main objectives of maritime management: The blue economy narrative centred on economic growth as a driver for increasing well-being and social sustainability on one hand and on the other, the ecosystem- based narrative centred on healthy maritime environments, assuring their intact functioning and the provision of ecosystem services (Lieberknecht 2020). According to the OECD, the status of ocean ecosystems will define how productive and efficient the future ocean economy will be (OECD 2016). Hence, damage to ocean ecosystems can act as a draw on the growth of the ocean economy, and comprise a risk to future growth and human well-being (Patil et al. 2018).

Fig.2. The Blue Doughnut - Source: Lieberknecht (2020) adopted from Raworth (2017)

Fig.2. The Blue Doughnut - Source: Lieberknecht (2020) adopted from Raworth (2017)Lieberknecht takes an adapted approach of the doughnut economy model by Raworth (2017), who defines this concept as a safe and just space for humanity (Raworth 2017). According to the approach of Lieberknecht, a sustainable blue economy must shift away from growth as the central objective, towards a focus on ensuring the plurality of environmental, social and human well-being objectives. The central aim of this blue doughnut economy is to achieve a fair distribution of human wellbeing within maritime ecosystem boundaries (Liebernecht 2020). This is a rather critical approach to growth as a paradigm of unlimited wealth generation. According to the doughnut concept, growth should instead be limited by environmental boundaries that cannot be transgressed and benchmarks for social well-being that cannot be undercut (Rockström et al. 2009, Raworth 2017, Lieberknecht 2020).

According to Lieberknecht (2020), a safe und just blue economy based on the doughnut concept ideally is distributive, generative and circular. In Figure 2, the outer boundary represents “the ecosystem boundaries that cannot be transgressed, with universally applicable planetary boundaries, located along the top half, and local ecosystem boundaries (which need to be defined for each specific study area) [...] along the bottom half”. The inner boundary represents “universally applicable wellbeing benchmarks that form the social foundation below which no human should fall.” (Lieberknecht 2020 p.10). Thus, a blue economy should contribute to this social foundation, while safeguarding both the planetary and the local ecosystem boundaries. The local applicability of the approach is particularly interesting. Next do defining local and regional ecosystem boundaries, this includes to prioritize investments and activities, that:

- most directly address human well-being shortfalls,

- most reduce contributions to existing planetary ecosystem boundary overshoots,

- sustain or restore local maritime ecosystems,

- prevent local environmental degradation.

Local activities within a blue economy should also serve a wide range of people-centred goals and ecosystem objectives, including:

- Maintaining, restoring and protecting the productivity, resilience, core functions, diversity, and intrinsic value of maritime ecosystems, thus safeguarding the natural capital upon which the blue economy and economic prosperity depend.

- Providing social-economic benefits for current and future generations, by contributing to poverty eradication, sustaining livelihoods, income, employment, health, safety, equity and food security (Lieberknecht 2020, WWF 2015).

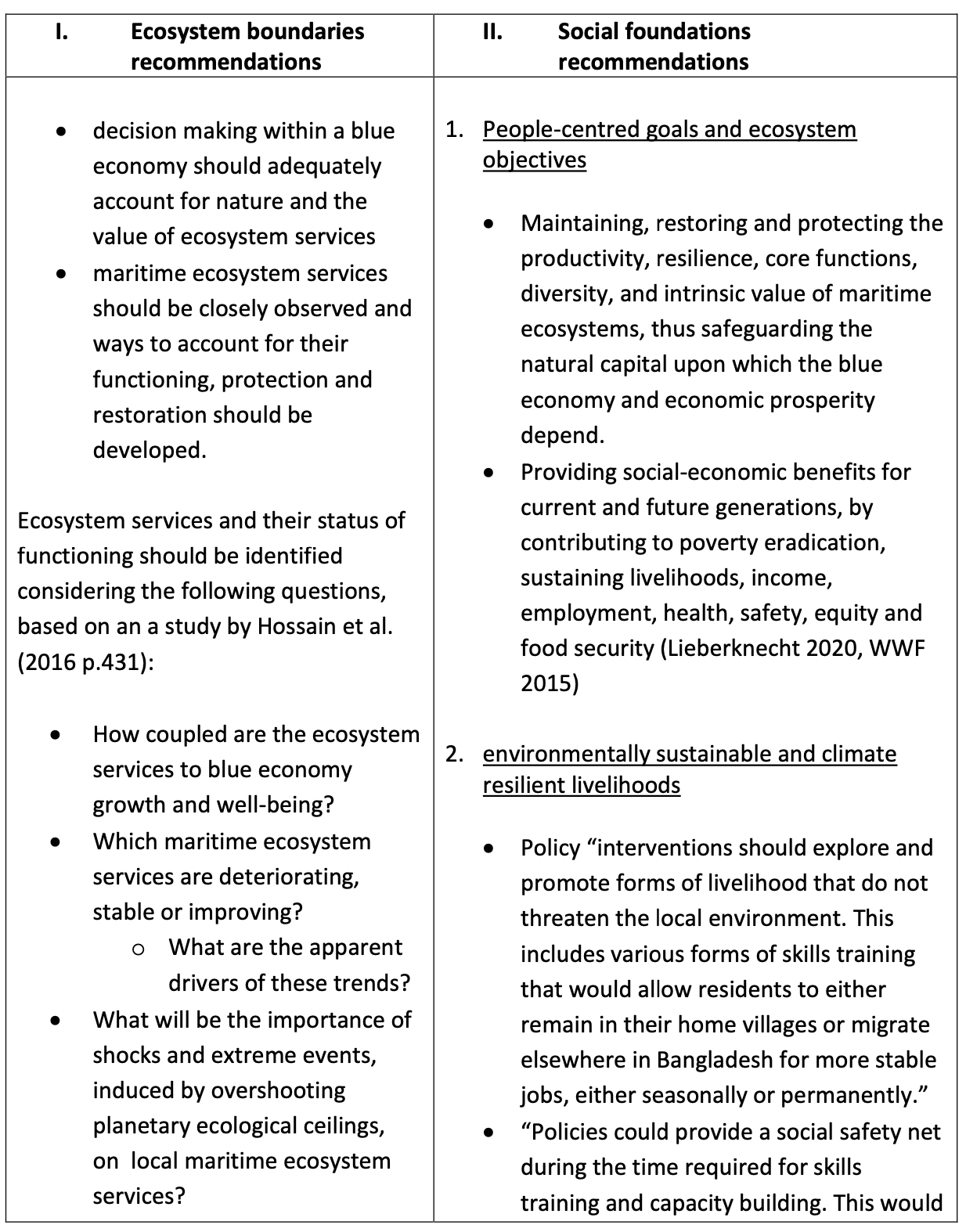

IV. Recommendations for the Blue Economy of Bangladesh

As existing studies and research trends are largely focused on the vast growth potential and the economic possibilities of exploiting Bangladesh’s maritime resources (hier noch Verweise einfügen), the following section deals with identifying recommendations from existing literature that can serve as starting points for defining I. the local ecological ceiling and building policies that accurately address issues of II. planetary boundaries and socio- economic considerations.

a. Local and regional ecological ceiling

The range of opportunities and risks to achieving Bangladesh’s blue economy objectives is dauntingly complicated. Complex land-sea interactions within the large coastal areas and the deltas of the GBM Basin, make it difficult to draw a clear differentiation from other sectors. Even measuring the output of the blue economy in Bangladesh thus remains challenging ( Patil et al. 2018) and currently only the following sectors are considered in the economic output:

- Tourism and Recreation, 25%

- Ship and Boat Building/breaking, 9%

- Transport, 22 %

- Marine Fisheries and Aquaculture, 22%

- Minerals, 3 %

- Energy, 19 %

According to the Patil et al., these measures are incomplete for a number of reasons. First, the measures are lacking a number of ecosystem services that may constitute a significant portion of the ocean economy, e.g. coastal protection services of the Sundarban mangroves, or carbon sequestration. These ecosystem services may provide a value of 286 million USD over 20 years (Patil et al. 2018). Secondly, the measures do not consider costs of environmental degradation resulting from various activities in the ocean economy. According to the Patil et al. (2018), a more accurate measure of economic output from the blue economy would include both the values of ecosystem services, and the negative costs of environmental degradation. This is presented in figure 3.

Fig.3. Annual Output from Bangladesh’s Ocean Economy, Incorporating Costs of Environmental Degradation. Source: Patil et al. (2018), p. 59

Fig.3. Annual Output from Bangladesh’s Ocean Economy, Incorporating Costs of Environmental Degradation. Source: Patil et al. (2018), p. 59Existing studies already found that human activities in maritime ecosystems will potentially affect the future output of Bangladesh’s blue economy in a negative way (BOBLME 2012, Patil et al. 2018). Mutually reinforcing and significant local human drivers of change are negatively altering the status of Bangladesh’s natural capital. These drivers include pollution from land- based sources, coastal development including the alteration of natural environments for aquaculture, and increasing fishing effort and capacity including illegal fishing and ecologically damaging fishing practices (BOBLME 2011). These local drivers are also interconnected to the global drivers of demographic changes, changes in global markets and economies, progress in science and technology, and global trends in human activities risking to overshoot planetary boundaries, such as climate change (Patil et al. 2018).

Although it is recognized that these drivers have damaging impacts on Bangladesh’s maritime ecosystems, concrete measurements and knowledge on the extend of these damages remain challenging and unclear. Particularly, there is also a lack of identifying the value of maritime ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration and coastal protection, water quality preservation, pollution filtering, biodiversity maintenance, food provisioning; all of which contribute to human well-being (Patil et al. 2018; Sarker et al. 2019). Maritime ecosystem services and their economic importance in general remain poorly understood and there is a need for extending research efforts in this regard.

According to Zhang et al., environmental degradation and the loss of ecosystem services in Bangladesh could eventually drive declines in economically important sectors such as shrimp and fish production, thus resulting in growing unsustainability across the whole social- ecological system (Zhang et al. 2015).

Considering these reasons, it is argued that a good functioning of all ecosystem services should be considered as the local ecological ceilings of Bangladesh’s blue economy. These ecosystem services and their status of functioning should be defined considering the following questions, based on an a study by Hossain et al. (2016 p.431):

- How coupled are the ecosystem services to blue economy growth and well-being?

- Which maritime ecosystem services are deteriorating, stable or improving? - What are the apparent drivers of these trends?

- What will be the importance of shocks and extreme events, induced by overshooting planetary ecological ceilings, on local maritime ecosystem services?

- Which are the ‘slow’ and ‘fast’ variables (i.e. how is the economic activity directly damaging the ecosystem services and which ones)?

- What are the implications for maritime management strategies?

Within Bangladesh’s blue economy, investments and activities should be prioritized that have a minimal negative impact on the maritime ecosystem services, or that even prevent environmental degradation and a loss of those services. This recommendation is also in line with the ocean as natural capital discourse identified by Silver et al. (2015), that calls for:

- decision making within a blue economy to adequately account for nature and the value of ecosystem services

- closely observing maritime ecosystem services and to develop ways to account for their functioning, protection and restoration.

a. Planetary Boundaries and socio-economic considerations

It is already widely recognized that Bangladesh is severely affected by climate change. Overshooting this planetary boundary will increasingly drive extreme weather events, such as cyclones and will also result in severe sea level rise, increasing numbers of droughts, erosion, tidal surge, saline water intrusion, floods, changes in precipitation trends and in ocean acidification. Although Bangladesh only contributes 0,31% to global GHG emissions, the country will be exposed to all of these aspects of climate change.

Considering these impacts, the blue economy should also be developed into climate change resilient economic practices, making it a driver for a resilient national economy (Sarker et al. 2019). This may also include securing and diversifying sources of income, as livelihoods may be destroyed by deteriorating and changing ecosystems that are negatively affected by human activities and climate change. Cyclones, tidal floods and erosion in coastal areas are already today forcing people to change their livelihoods in Bangladesh, often towards illegal behaviour and activities damaging the country’s ecosystems, such as catching shrimps and fish from wild source and wood logging from the Sundarbans (Ahmed et al. 2019).

In addition to environmental disasters resulting from natural drivers and global environmental change trends, human interventions are also negatively affecting livelihoods in Bangladesh. For example, expanding the shrimp farming industry is already limiting the livelihood opportunities of people, because it leads to increasing soil salinity, which prevents people from engaging in subsistence agriculture (Ahmed et al. 2019, Paprocki & Cons 2014).

Today, a majority of the population in Bangladesh’s coastal region relies on fishing and shrimp farming as their major means of livelihood. However, a significant proportion of the population also relies on wild shrimp collection, and in wood logging around the coastal regions due to a lack of work and income opportunities (Ahmed et al. 2019). Within the vulnerable and climate sensitive coastal ecosystem of Bangladesh’s coasts, this situation should be worrying and calls for people-centred conservation efforts (Ahmed et al. 2019, Lieberknecht 2020). There is substantial evidence that natural infrastructure, such as mangroves, not only serve as protectors against floods and erosion, but also provide many other co-benefits such as fishery habitat, carbon sequestration and storage, and water quality improvements (Sutton-Grier et al. 2015). If such natural infrastructure is however damaged or destroyed by human activities as a consequence of poverty and a lack of other means of income, Bangladesh’s blue economy should aim at solutions that both contribute to a healthy environment and supporting social foundations.

According to Silver et al. (2015) and Lieberknecht (2020), Local activities within a blue economy should serve a wide range of people-centred goals and ecosystem objectives, because coastal and maritime diversity is important to sustain livelihoods. This range of goals and objectives should include:

- Maintaining, restoring and protecting the productivity, resilience, core functions, diversity, and intrinsic value of maritime ecosystems, thus safeguarding the natural capital upon which the blue economy and economic prosperity depend.

- Providing social-economic benefits for current and future generations, by contributing to poverty eradication, sustaining livelihoods, income, employment, health, safety, equity and food security (Lieberknecht 2020, WWF 2015).

Additionally, Ahmed et al. (2019) call for appropriate policies aimed at providing environmentally sustainable and climate resilient livelihoods of Bangladesh’s coastal inhabitants, instead of criminalizing illegal activities that only increase their vulnerability:

- Policy “interventions should explore and promote forms of livelihood that do not threaten the local environment. This includes various forms of skills training that would allow residents to either remain in their home villages or migrate elsewhere in Bangladesh for more stable jobs, either seasonally or permanently.”

- “Policies could provide a social safety net during the time required for skills training and capacity building. This would allow residents to acquire new skills necessary for different alternative livelihoods comfortably. At the macro-level, this may require rethinking investments into the southwest region of Bangladesh that provide ample job opportunities and lifestyle satisfaction for residents” (Ahmed et al. 2019, p.914).

This adds to the oceans as SSF livelihoods discourse identified by Silver et al. (2015), which points out the need for a good understanding of the social impacts of blue economy policies and activities. SSF are considered as providing food for the poor, employment for fishers as well as providing work and income for women (Silver et al. 2015). Thus, blue economy policies in Bangladesh, that are concerned with the fishing sector, should consider the systematic integration of SSF in blue economy decision-making and fisheries management, which may include:

- carefully integrating fishers’ concerns and participation in decision making,

- recognizing local knowledge and enabling territorial access to ocean spaces

- a careful consideration of common goods and property rights, while addressing issues of uncertainty, overcapacity and inefficiency

V. Conclusion

This article identified global discourses on social and environmental sustainability in blue economies and projected these discourses on the emerging blue economy in Bangladesh, providing recommendations for how the country could take an approach of blue economic development that stays within the ecosystem boundaries of the (blue) doughnut economy model of Raworth (2018) and Lieberknecht (2020).

Two dimensions where identified, that need further research. These include the overall consideration and economic measurement of maritime ecosystem services, and the social dimensions of blue economy policies in Bangladesh.

This article however does not analyse existing national blue economy policies and strategies, such as the 7th FYP of Bangladesh. Hence it does not identify, to which extent existing plans of the GoB are already considering the identified recommendations. The article also does not give a lot of consideration on the economic growth potential of Bangladesh’s blue economy. Instead, it aims at identifying recommendations to how the blue economy of the country could be conceptualized under the blue doughnut model, considering ecosystem boundaries and social foundations. In the following table, these recommendations are summarized:

Glossary

EEZ – Exclusive Economic Zone

FYP – Five Year Plan of Bangladesh

GoB – Government of Bangladesh

GBM Basin – Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Basin

GHG – Greenhouse gas

OECD - Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Rio +20 Summit – 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development

SSF – small scale fisheries

SoNG – Swatch of No Ground

References

- Ahmed, I., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., van der Geest, K., Huq, S., & Jordan, J. C. (2019). Climate change, environmental stress and loss of livelihoods can push people towards illegal activities: a case study from coastal Bangladesh. Climate and Development, 11(10), 907– 917. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1586638

- Alam, M. W., Xiangmin, X., Ahamed, R., Mozumder, M. M. H., & Schneider, P. (2021). Ocean governance in Bangladesh: Necessities to implement structure, policy guidelines, and actions for ocean and coastal management. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 45, 101822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsma.2021.101822

- Alam, M. K. (2014). Ocean/blue economy for Bangladesh. MAU, MOFA, 1-13

- Awal, M.A., Islam, A.F.M.T., 2020. Water logging in south-western coastal region of Bangladesh: Causes and consequences and people’s response. Asi. J. Geogr. Res. 3 (2), 9– 28. http://dx.doi.org/10.9734/ajgr/2020/v3i230102

- Barange, M., Fernandes, J.A., Kay, S., Hossain, M.A.R., Ahmed, M., Lauria, V. (2018). Marine Ecosystems and Fisheries: Trends and Prospects. In: Nicholls, R., Hutton, C., Adger, W., Hanson, S., Rahman, M., Salehin, M. (eds) Ecosystem Services for Well-Being in Deltas. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71093-8_25

- BOBLME. (2011) TDA Synthesis Report. Report No.: BOBLME-2012-Project-01.

- Cheung, W. W., Lam, V. W., Sarmiento, J. L., Kearney, K., Watson, R., & Pauly, D. (2009). Projecting global marine biodiversity impacts under climate change scenarios. Fish and Fisheries, 10(3), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2008.00315.x

- Chawdhury, D.D., Rokanuzzaman, M. (2018). Fishing as a Part of Blue Economy. Blue Economy: Problems and Prospects of Marine Fisheries in Bangladesh (pp.1-30), Academic Press and Publishers Library (APPL)

- The Guardian (2022). Bangladesh is paying a high price for developed world’s carbon emissions. The Guardian Website. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jul/10/bangladesh-is-paying-a-high- price-for-developed-worlds-carbon-emissions, retrieved on 22-08-2022.

- Hossain, M. S., Dearing, J. A., Rahman, M. M., & Salehin, M. (2015). Recent changes in ecosystem services and human well-being in the Bangladesh coastal zone. Regional Environmental Change, 16(2), 429–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0748-z

- Jafrin, N., Abu, N. M. S., Hossain, M. I. (2016). Blue economy in Bangladesh: proposed model and policy recommendations. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 7 (21), 131-135.

- Guinotte, J. M., & Fabry, V. J. (2008). Ocean Acidification and Its Potential Effects on Marine Ecosystems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1134(1), 320–342. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1439.013

- Helmholtz Klimainitiative (2022). Planetare Grenzen: Neun Leitplanken für die Zukunft. https://helmholtz-klima.de/planetare-belastungs-grenzen

- Hussain, M. G., Failler, P., & Sarker, S. (2019). Future Importance of Maritime Activities in Bangladesh. Journal of Ocean and Coastal Economics, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.15351/2373-8456.1104

- Lieberknecht, L.M. (2020). Ecosystem-Based Integrated Ocean Management: A Framework for Sustainable Ocean Economy Development. A report for WWF-Norway by GRID-Arendal. https://www.grida.no/publications/477

- Nash, K. L., van Putten, I., Alexander, K. A., Bettiol, S., Cvitanovic, C., Farmery, A. K., Flies, E. J., Ison, S., Kelly, R., Mackay, M., Murray, L., Norris, K., Robinson, L. M., Scott, J., Ward, D., & Vince, J. (2021). Oceans and society: feedbacks between ocean and human health. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 32(1), 161–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160- 021-09669-5

- Patil, P. G., Virdin, J., Colgan, C. S., Hussain, M. G., Failler, P., & Veigh, T. (2019). Initial Measures of the Economic Activity Linked to Bangladesh’s Ocean Space, and Implications for the Country’s Blue Economy Policy Objectives. Journal of Ocean and Coastal Economics, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.15351/2373-8456.1119

- Patil, P. G., Virdin, J., Colgan, C. S., Hussain, M. G., Failler, P., & Veigh, T. (2018). Toward a Blue Economy: A Pathway for Sustainable Growth in Bangladesh. Washington, DC: The World Bank Group.

- Paprocki, K., & Cons, J. (2014). Life in a shrimp zone: Aqua- and other cultures of Bangladesh’s coastal landscape. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 41(6), 1109–1130.

- Raworth, K. (2018). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. Random House Business.

- Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin III, F.S., Lambin, E.F. et al. 2009a. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature, 461(7263), 472.

- Sarker, S., Hussain, F.A., Assaduzzaman, M., Failler, P., 2019. Blue economy and climate change: Bangladesh perspective. J. Oce. Coas. Econ. 6 (2), http://dx.doi.org/10.15351/2373-8456.1105

- Silver, J. J., Gray, N. J., Campbell, L. M., Fairbanks, L. W., & Gruby, R. L. (2015). Blue Economy and Competing Discourses in International Oceans Governance. The Journal of Environment & Development, 24(2), 135–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496515580797

- Sutton-Grier, A. E., Wowk, K., & Bamford, H. (2015). Future of our coasts: The potential for natural and hybrid infrastructure to enhance the resilience of our coastal communities, economies and ecosystems. Environmental Science & Policy, 51, 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.04.006

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019. Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/423). https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Highlights.pdf

- Wan, Z., el Makhloufi, A., Chen, Y., & Tang, J. (2018). Decarbonizing the international shipping industry: Solutions and policy recommendations. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 126, 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.11.064

- World Bank, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2017). The Potential of the Blue Economy : Increasing Long-term Benefits of the Sustainable Use of Marine Resources for Small Island Developing States and Coastal Least Developed Countries. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/26843

- WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature) (2015). Principles for a sustainable blue economy. http://wwf.panda.org/?247477/Principles-for-a-Sustainable-Blue-Economy.

- Zhang, K., Dearing, J. A., Dawson, T. P., Dong, X., Yang, X., & Zhang, W. (2015). Poverty alleviation strategies in eastern China lead to critical ecological dynamics. Science of The Total Environment, 506–507, 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.10.096