“SAVE THE BEES", BUT WHICH ONES? - The European Federation of Dark Bee Conservatorie (FEDCAN), a french initiative to fight beewashing and reintegrate the black bee into European biodiversity

Updated at 31.08.2022

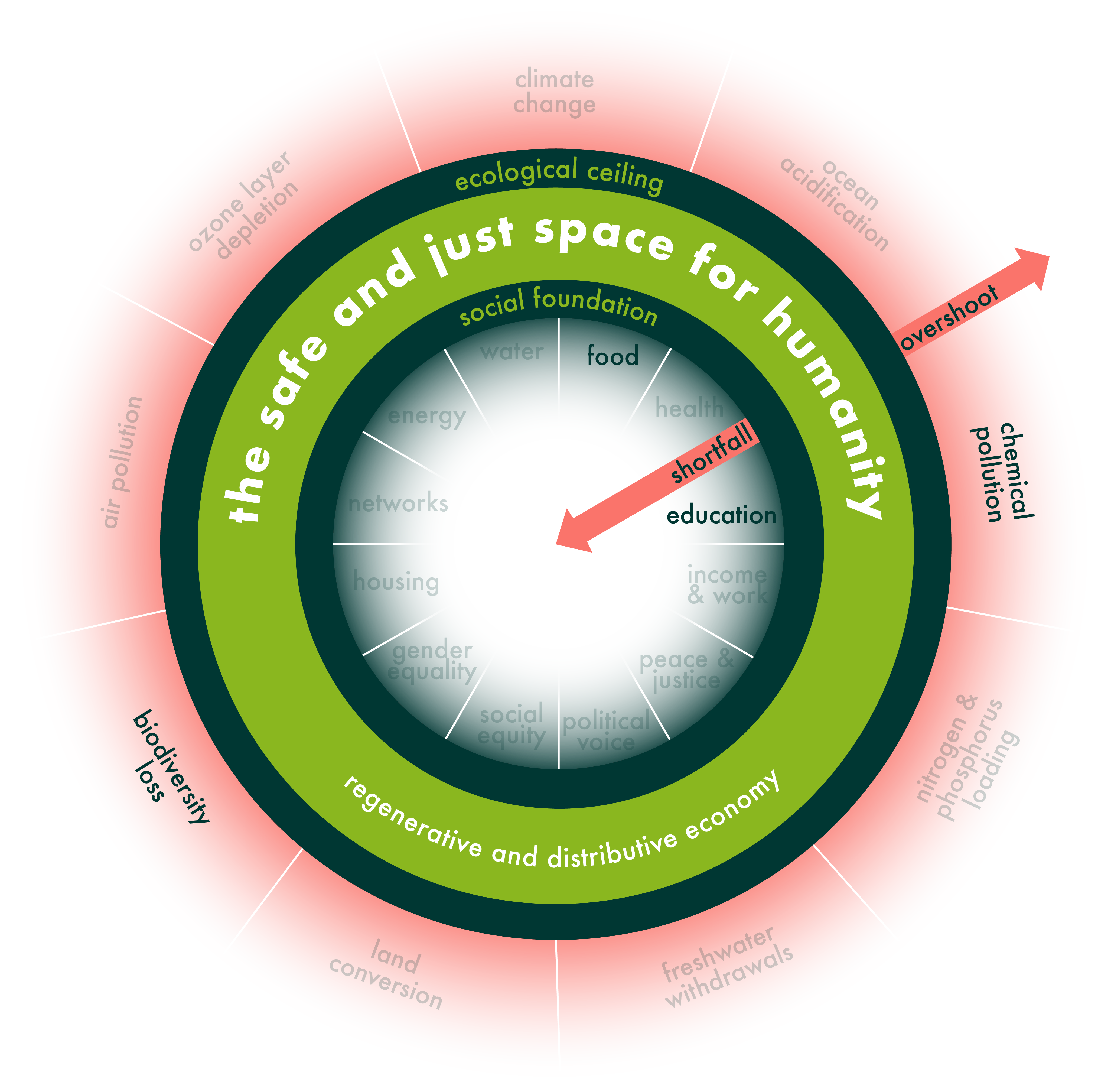

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subject

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subjectBees made by and for humans

“Bees are turning yellow”. So said a beekeeper I met at a local market in Limoges, France. This change in color, which can be observed today in almost all of Europe, is due to the numerous genetic crosses and selection work carried out between different subspecies of bees in order to obtain a particular species of bee that is not very aggressive, resistant and, above all, productive. One moves from a native European bee described as "black" to a more yellow non-native bee due to its crossing with other less aggressive species.

Indeed, within the families of pollinating insects, the genus "Apis" is distinguished in 7 species of bees, including the Apis mellifera, which itself includes 26 subspecies. Among these subspecies, some are known for being gentle, having a low tendency to swarm and being sensitive to cold and diseases: this is the Apis mellifera ligustica, the Italian bee. In contrast, the Apis mellifera mellifera, the European black bee, is known for its high disease resistance, aggressiveness, and high tendency to swarm (Roy & Vilagines, 2015).

It is worth noting that subspecies are very important within an ecosystem. They have developed morphological and behavioral characteristics that allow them to adjust to their environment and pollinate a large number of flowers and crops in a specific climate and time of year (Büchler et al, 2010).

In order to create the ideal conditions for an economically profitable production of honey, some subspecies (mainly the black bee and the Italian bee) have been genetically crossed in the 20th century to obtain the so-called "Buckfast" bee (Toullec, 2008), one of the most widespread crossbreeding in the world (Roy; Vilagines, 2015), which results in a productive and not very aggressive bee, made "by man and for man" (Elie, 2021).

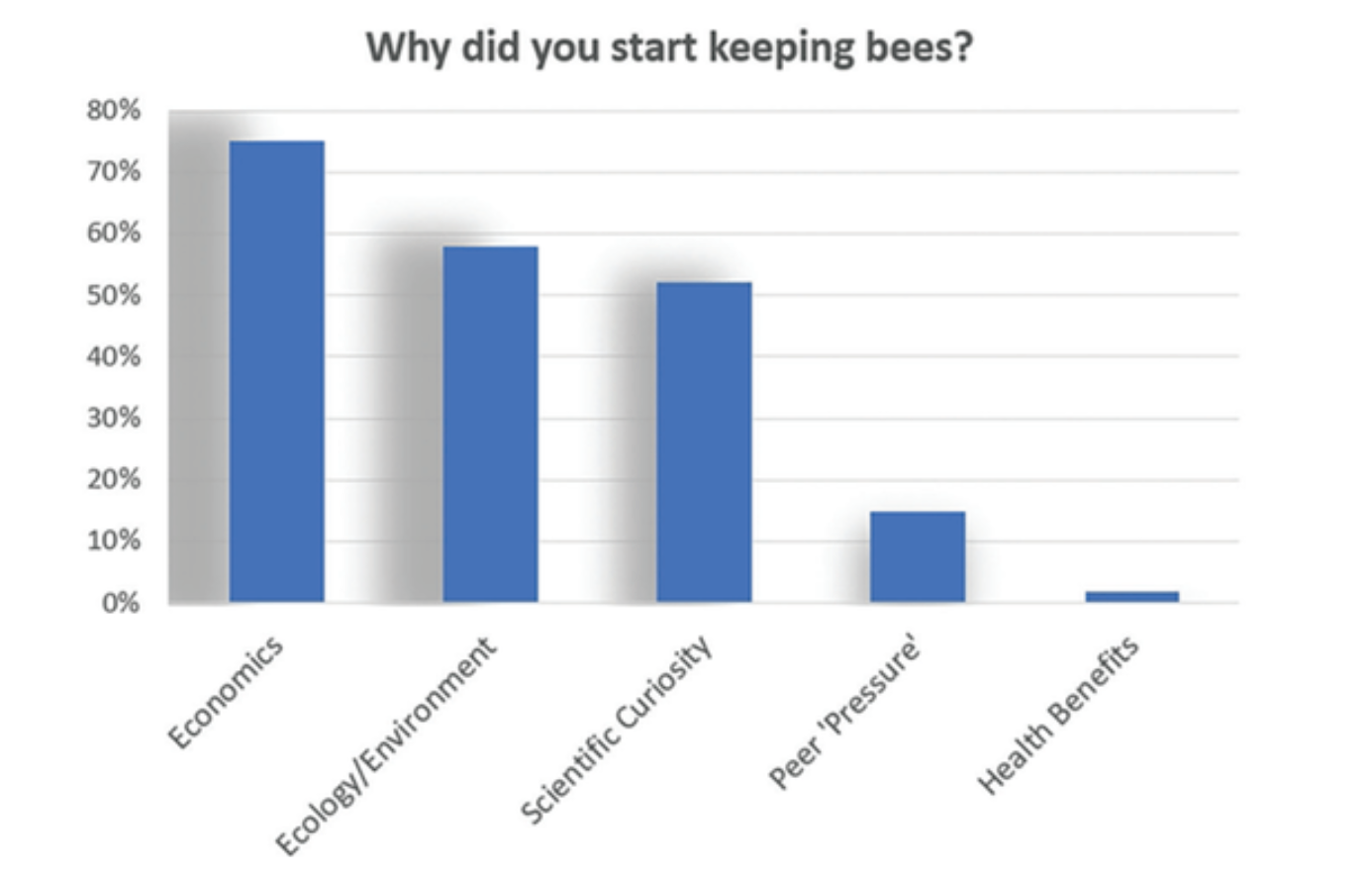

Genetic selection (including artificial insemination and importation of fertilized queens) among subspecies is nowadays one of the pillars of modern beekeeping. It is partly through this process that the bee becomes a "domesticated animal", with its fate entirely dependent on the person manipulating its genes (Garnery, 2019). Indeed, the Buckfast bee is less aggressive and produces significantly more honey, but its genetic crossing makes it more fragile and vulnerable to winter conditions - which consequently makes it dependent on the human who feeds it. Among other factors, the introduction of new pesticides in the 1990s has caused beekeepers to suffer significant losses of their local bee colonies and therefore to rely on the massive and partially uncontrolled importation of hybrid and non-native bees, which automatically accelerates the hybridization of subspecies. (Garnery, 2019).In addition, urban and hobby beekeeping has increased in recent years - mainly for economic reasons due to the profitability of the Buckfast bee as described in the graph below (Miksha,2021). As a matter of fact, there is now an amazing population growth of managed honey bees - mostly the Buckfast - in places where there is not a native insect (Miksha, 2021). This improved subspecies allows a high productivity of honey and its widespread presence throughout the world ensures a part of the pollination of the crops.

As such, the honey bee is now seen as a considerable economic opportunity for commercial pollination and honey production, which is greatly increasing in its exploitation on a global scale.

Fig. 1. Miksha, Ron. (2021). Keeping bees for the wrong reasons: American Bee Journal April 2021. American Bee Journal. 161. 433-437.

Fig. 1. Miksha, Ron. (2021). Keeping bees for the wrong reasons: American Bee Journal April 2021. American Bee Journal. 161. 433-437.However, the importation of bees is not fully controlled and much uncertainty remains about the provenance of imported queens and swarms (Laarman, 2019). Moreover, such breeding processes result in the artificial introduction of "improved" bees into an ecosystem with its own native bee population. Introducing a foreign species - nourished like any other farmed animal - in large quantities into natural areas or cities is equivalent to introducing an efficient and advantaged competitor into an ecosystem with already struggling native populations (there are about 865 species of wild bees in France) (Lemoine, 2010). In addition, managed honeybees can transmit particularly harmful viruses to native species, thus increasing their vulnerability (Garnery, 2019). We therefore speak of "genetic pollution" (Roy; Vilagines, 2015) to describe the increasing invasion of Buckfast bee populations into local ecosystems. The improved bee is certainly of economic interest, is a popular hobby for city dwellers and conveys the image of preserved nature. However, it represents a real saturation of natural spaces that is leading to the alarming disappearance of local species such as the Apis mellifera mellifera, the European black bee (Lemoine, 2010).

The buzz is missing for the Black Bee

Bees are nowadays a symbol of the alarming loss of insect biodiversity in fields, orchards and gardens. Indeed, they are in contact with many agents of the environment and therefore very exposed to human activities (Hristov, 2021). Among the increasing threats, we can mention high temperatures, droughts in summer (causing heat stress for the plants providing the nectar) and parasites and diseases like the Varroa destructor. Bees are also victims of the intensification of beekeeping due to stressful transhumance, artificial insemination, colony importation and the annual or biennial elimination of queens (Elie, 2021).

They are also threatened by agriculture and its massive impacts through the expansion of monocultures: this is known as habitat loss and fragmentation and especially the lack of diversity leading to a very poor nutrition (Hristov, 2021).

The bee as a symbol of the disappearance of biodiversity is thus leading to a growing public interest in this well-known pollinating insect. However, the public interest falls victim to a wave of misinformation regarding the protection of the bee: it is not only about protecting the domestic honey bee, a managed species of bee (usually Buckfast) which is already nourished by man, but also about protecting the native subspecies of bees, which are not genetically modified by man and are threatened by current industrial beekeeping and agriculture.

This is a phenomenon that MacIvor and Packer call "bee washing" i.e. "greenwashing as applied to potentially misleading claims for augmentation of native and wild bee populations" (MacIvor & Packer, 2015). The "buzz" around the endangered bee allows companies to improve their "environment-friendly" marketing image while promoting the exploitation of managed bees to the detriment of wild native bees - in the case of Europe, to the detriment of the black bee.

Save the bees, but which ones?

One often notices the inscription "save the bees", or "bees friendly" on the labels of commercial products. Many companies are indeed seizing this "environmental publicity opportunity" (Miksha, 2021) and invest in honey bees hives to build up an ecological appearance in line with current ecological "trends". The aim is to fool consumers by claiming to support beekeeping without providing scientific evidence of real support for native bees. In concrete terms, covering the roofs of a company with honey hives appears to be a gesture in favor of bees but does nothing to help local biodiversity as bees are generally managed species that contribute to the disappearance of local subspecies (Colla, 2021). Bee- washing leads to misplaced conservation practices, public misinformation and misallocation of resources as it encourages the public to invest in and therefore protect managed honey bee colonies (Colla, 2021). When thinking of buying a "bee-friendly" product, the consumer performs a "feel good action" that in fact is harming native bee populations already under threat.

Bee-washing usually consists of widespread initiatives and campaigns following the already known principle of "greenwashing" that highlights the essential difference between "looking good" and "being good" (Miksha, 2021).

Flowhives, rooftop honeybee hives in cities or bee hotels, are public "attention grabbers", i.e., examples of so-called "ecological" beekeeping that have flooded the market in the last decades.

However, none of these examples is aiming at bee's survival and protection but rather at the economic contribution of an industrial honey produced by man-made colonies.

Above all, none of these examples have scientific evidence of real protection of endangered bee subspecies. There is a real need for scientific research in the area of long term and sustainable protection of local and native bees. (MacIvor; Packer, 2015).

Who is Apis mellifera mellifera, the black bee native to Europe?

The black bee, present between the Pyrenees and Scandinavia for about 1 million years (Garnery, 2019) is a native European bee, dark in appearance and adapted to cold winter climates. It is now in a critical condition in France and Europe. It suffers from a bad reputation among beekeepers (aggressiveness, low honey production) and is therefore progressively replaced by a massive importation of swarms of hybrid bees (therefore more fragile and less autonomous), which, artificially introduced into an ecosystem, are leading to its disappearance (Canova, 2019).

Fig. 2. CONSERVATORY OF THE BLACK BEE IN VAL DE LOIRE, SOLOGNE (FRANCE)

Fig. 2. CONSERVATORY OF THE BLACK BEE IN VAL DE LOIRE, SOLOGNE (FRANCE)The fedcan and the doughnut economy

In order to restore the diversity of the black bee's genetic heritage in France and to preserve its local subspecies, conservation and reintroduction projects have been set up in France and in some European countries (e.g., UK, Denmark).

Among others, several French associations called "Conservatories of the Black Bee" and the NGO Pollinis gathered in a European Federation in December 2015. The FEDCAN (Fédération Européenne Des Conservatoires de l'Abeille Noire) is nowadays aiming at promoting and protecting the black bee as an endemic species from Western Europe.

The principle of the "Conservatory" is simple: it consists in setting up a "close- to-nature" beekeeping method to protect and recover the genetic diversity of the black bee.

Conservatories create areas protected from the previously mentioned genetic pollution in order to conserve local subspecies and, in the long run, export them back out of the preservation area to reinsert the black bee into Europe and "blacken the local population" (Canova, 2019). In the protected areas, overfeeding, artificial maintenance of colonies during the winter, the purchase of queens and the import of non-local bees, insemination or even transhumance are prohibited.

The aim is to combat the industrial model of beekeeping and to prevent bees from being in direct contact with intensive agriculture. The main goal of this initiative is to increase the number of conservatories in Europe in order to reduce the artificial hybridization mentioned above. Nevertheless, the federation also plans to increase the legal recognition of the conservatories' status. Indeed, the only way to obtain an effective protection of the black bee is to create a regulated zone in which no other genetic source will be imported. The Federation is now fighting to extend the core protection zone. There is, therefore, an urgent need to obtain official legal protection status to protect conservancy areas from the importation of foreign bees (Laarman, 2019).

In addition, the Federation conducts education and awareness actions with both the public and beekeepers regarding the incredible genetic diversity of the black bee and the dangers of extinction that threaten it today. These awareness-raising actions are contributing to reducing beewashing advertisements by showing the consumers the qualities and importance of the local black bee in comparison with the managed species.

Moreover, the principle of the Conservatory is part of a long-term project (i.e., the protection and then the reintegration of black bees in France and in Europe) and brings together various societal actors at different levels: it includes beekeepers as well as the bees, and the general public as well as various legislative and governmental actors to obtain the legal recognition mentioned above. This is shown by the doughnut designed by Rupprecht et al (2020) to illustrate bees as full participants in the human-wildlife coexistence space - and the environmental issues they face today.

In its fight to conserve and reintegrate the black bee, the FEDCAN is part of the holistic scope of the doughnut economy, seeking to move away from a utilitarian perception of nature to a broadened concept of sustainability, i.e., a space for human-wildlife coexistence - as shown in the diagram above (Rupprecht et al., 2020). Thanks to the FEDCAN project, bees do not enter commercial and environmental negotiations in an indirect way (as a simple pollinator or honey producer), but are considered in the holistic vision of all their subspecies as essential to achieving human well-being. It is a question of considering well-being as "relation-based, not resourced based" (Rupprecht et al., 2020) and of knowing how to differentiate "beekeeping" from "bee exploitation" (Elie, 2021).

Position of the black conservatories withing the doughnut economy

The project of these black bee conservatories addresses different parts of the doughnut economy that are considered to be in shortfall, such as "food" (e.g., honey production) and "education" through the many awareness-raising workshops organized for the general public or amateur beekeepers. They also address other parts that go beyond the ecological ceiling represented in the chart, such as "chemical pollution" regarding pesticides on agricultural land, "land conversion", "biodiversity loss" and "air pollution".

The very concept of the black bee conservatory finds its place within the doughnut as it is about re- establishing and using ecological services that are essential for human well-being (pollination and honey harvesting) without altering or destroying the place and agents of production. Bees are therefore not only considered as a resource but also as a set of native subspecies playing an essential role in human well-being thanks to the various ecological services provided such as pollination, production of food and medical products as well as sharing cultural and social values.

Check out the stylized pdf version of this article as well!References

- Astier, M. (2017, 18 juin). Il faut sauver l’abeille noire. Reporterre, le quotidien de l’écologie. https://reporterre.net/Il-faut-sauver-l-abeille- noire

- Büchler, R., Berg, S., & le Conte, Y. (2010). Breeding for resistance toVarroa destructorin Europe. Apidologie, 41(3), 393‐408. https://doi.org/10.1051/apido/2010011

- Canova, V., Garnery, L., & Laarman, N. (2019, 2 avril). Abeilles en liberté - UN MAGAZINE AU SERVICE DE LA BIODIVERSITÉ ORDINAIRE - DOSSIER POURQUOI IL FAUT SAUVER L’ABEILLE NOIRE. https://canec.fr. Consulté le 20 août 2022, à l’adresse https://canec.fr/wp- content/uploads/2020/03/Revue-Abeilles-en-libert%C3%A9.pdf

- Colla, S. R. (2022). The potential consequences of ‘bee washing’ on wild bee health and conservation. International Journal for Parasitology : Parasites and Wildlife, 18, 30‐32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijppaw.2022.03.011

- Corbet, S. A., Williams, I. H., & Osborne, J. L. (1991). Bees and the Pollination of Crops and Wild Flowers in the European Community. Bee World, 72(2), 47‐59. https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772x.1991.11099079

- Hristov, P., Shumkova, R., Palova, N., & Neov, B. (2021). Honey bee colony losses : Why are honey bees disappearing ? Sociobiology, 68(1), 5851. https://doi.org/10.13102/sociobiology.v68i1.5851

- Importations d’abeilles depuis l’étranger : quelles règles ? (2018). Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Souveraineté alimentaire. https://agriculture.gouv.fr/importations-dabeilles-depuis-letranger- quelles-regles

- Khalifa, S. A. M., Elshafiey, E. H., Shetaia, A. A., El-Wahed, A. A. A., Algethami, A. F., Musharraf, S. G., AlAjmi, M. F., Zhao, C., Masry, S. H. D., Abdel-Daim, M. M., Halabi, M. F., Kai, G., al Naggar, Y., Bishr, M., Diab, M. A. M., & El-Seedi, H. R. (2021). Overview of Bee Pollination and Its Economic Value for Crop Production. Insects, 12(8), 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12080688

- L’abeille noire a trouvé refuge à Ouessant | bretagne-biodiversite.org. (2010). Bretagne biodiversité. https://bretagne-biodiversite.org/octobre/l-abeille- noire-a-trouve-refuge-a-ouessant.php

- LEMOINE G., 2012. Faut-il favoriser l’Abeille domestique (Apis mellifera) en ville et dans les écosystèmes naturels ? Le Héron, 43 (4-2010) : 248-256

- MacIvor, J. S., & Packer, L. (2015). ‘Bee Hotels’ as Tools for Native Pollinator Conservation : A Premature Verdict ? PLOS ONE, 10(3), e0122126. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122126

- Miksha, Ron. (2021). Keeping bees for the wrong reasons: American Bee Journal April 2021. American Bee Journal. 161. 433-437.

- Rupprecht, C. D. D., Vervoort, J., Berthelsen, C., Mangnus, A., Osborne, N., Thompson, K., Urushima, A. Y. F., Kóvskaya, M., Spiegelberg, M., Cristiano, S., Springett, J., Marschütz, B., Flies, E. J., McGreevy, S. R., Droz, L., Breed, M. F., Gan, J., Shinkai, R., & Kawai, A. (2020). Multispecies sustainability. Global Sustainability, 3. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.28

- Toullec, A.N.K. (2008) Abeille noire, Apis mellifera mellifera. Historique et sauvegarde. Thèse de Doctorat Vétérinaire, Faculté de Médecine de Créteil, 168.