Pleistocene Park - Back to the Ice Age : How primeval ecosystems could mitigate climate change

Updated at 27.08.2022

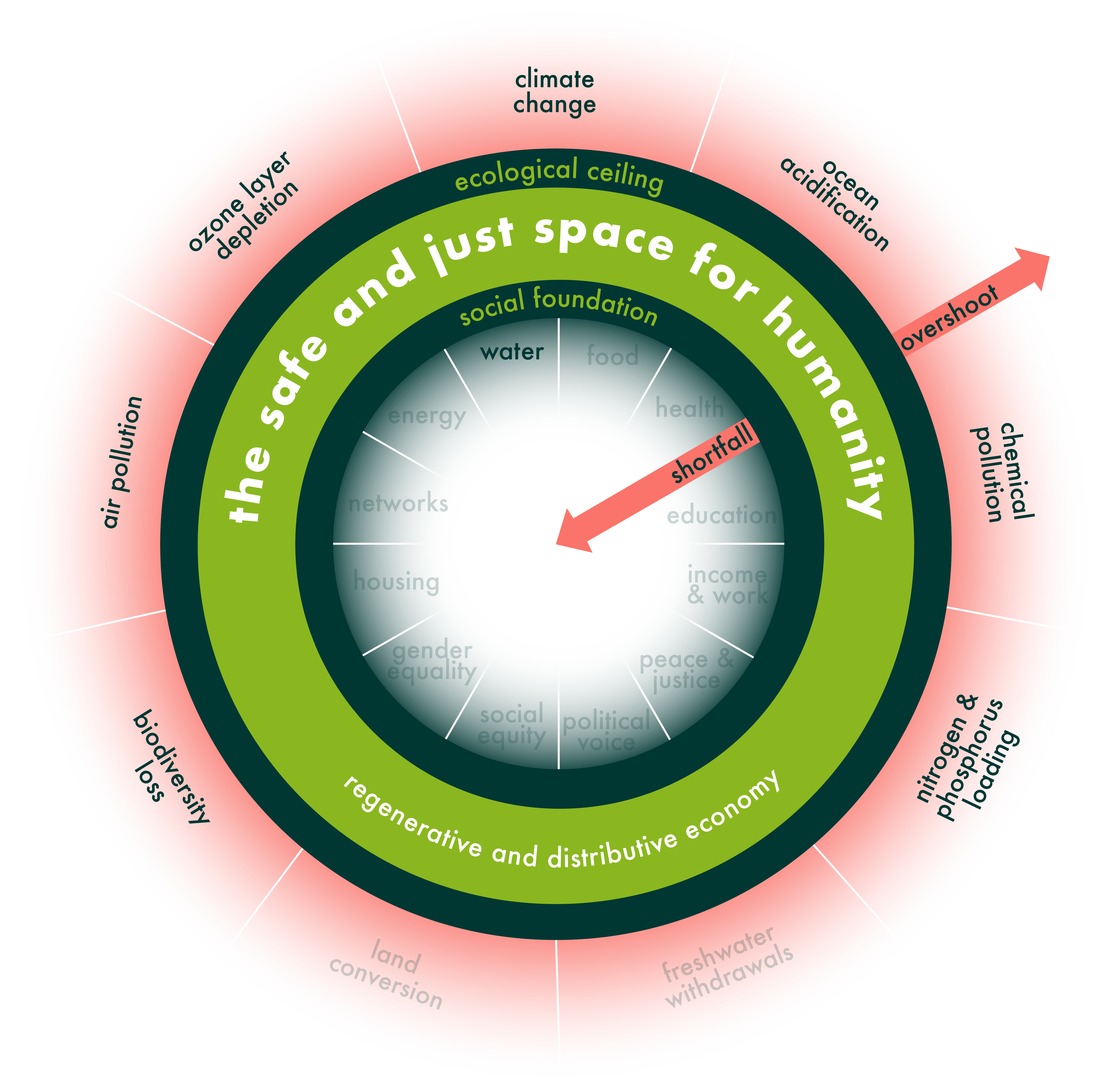

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subject

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subjectI. Introduction

Rapid climate change and biodiversity decline are major challenges to humankind and call for new approaches involving active nature management strategies that are able to secure the resilience of ecosystems (Macias-Fauria et al., 2020). That's why, more than 20 years ago, the Russian researcher Sergei Zimov started to create the Pleistocene Park in the North Siberian Arctic, a place where scientists are introducing bison, horses and other large herbivores. The four-legged landscapers are to transform today's tundra back into the grassy mammoth steppe as it had been covering large parts of the northern hemisphere in the Pleistocene era.

The reason for the desire to convert today's tundra back into a vast grassland is the rapidly thawing permafrost soil, which has been identified as a key source of greenhouse gases (GHG) and is therefore increasing atmosphere warming rapidly (Lucas & Enos, 2019).

II. (Historical) Background

During the Pleistocene – the last ice age - highly productive grazing ecosystems dominated most of the earth’s surface. On all continents, there were animal populations in such high densities which, in the present day, are only observable in some African national parks, e.g., the Serengeti. The largest of all these ecosystems was the so-called mammoth steppe. It stretched from Spain to Canada and from the Arctic islands to China. Millions of mammoths, bison, horses, reindeer, wolves and tigers kept the grasslands in ecological balance. Such an ecosystem can exist in a wide range of climates and has survived several ice ages and interglacial periods (Lundgren et al., 2020).

With the successful spread of (stone age) humans after the last ice age, the end of the Pleistocene, numerous herbivores became extinct. The technical progress of humankind was too fast and the animals had no defense strategy against the new predator. Of course, humans did not kill all the animals, but the intervention in the ecosystems was enough to bring it out of balance. One important reason for this is that in the Arctic, slow-growing plants cannot compete with faster growing plants. Here, the large herbivores, often heavier than 1000 kg, trampled the slow-growing plants flat, thus prevented forest growth and helped plowing up the earth with their hooves. Therefore, millions of square kilometers of highly productive grasslands with fertile soils disappeared. In this new environment, large herbivores like the mammoth or the woolly rhinoceros could no longer find enough food to survive the cold winters. With the beginning of the Holocene (era after the Pleistocene) not only the human population increased, but also the temperature and therefore the sea level rose and many of the migration routes on which mammoth and other animals could reconquer orphaned regions no longer existed. The individual populations became too small and gradually died out (Brook & Bowman, 2002; Galetti et al., 2018).

1. Recent Past

Even though it seems as if in the Arctic and especially in Siberia there is still a wild nature to be seen today it is not comparable with the Pleistocene era. Today's local ecosystem is home to only a fraction of species. This is due to the fact that the regions actual wild ecosystems were destroyed by humans over 10.000 years ago (Viering, 2021). Besides the local found, ecosystems in the Arctic are particularly affected by climate change, as the temperature increase here is above average. In recent decades, warming in the Arctic has been twice as high as the global average, especially in winter. Compared to other biomes, the Arctic is considered to be relatively constant over time and not very resilient to climate change. For this reason, the Arctic is particularly vulnerable to the relatively rapid, large scale climate change (IPBES, 2019).

The temperature increase causes the soils of the tundra to thaw more frequently and more quickly in summer. This is a problem in particular because the frozen ground contains between 1300 and 1600 gigatons of carbon. In comparison, the entire atmosphere currently contains around 800 gigatons of carbon. In addition, soils also contain other greenhouse gases such as methane (CH4), which has a greenhouse effect 30 times higher than CO2, and nitrous oxide (N2O), which has a greenhouse effect 300 times higher than CO2 (Turetsky et al., 2020). These figures illustrate why permafrost melting is counted among the tipping elements of climate change. If the permafrost area is reduced by 35% in 2080, as calculated, this could set in motion a positive feedback loop that can cannot be stopped (Miner et al., 2022).

2. Environmental Impact

In temperate latitudes, the carbon cycle functions in such a way that trees and plants absorb and store carbon from the air. When the plant then sheds its leaves or dies, microbes decompose the biomass and the carbon is released again. At this point, in very simplified terms, the carbon cycle begins again.

Overall, this cycle should be balanced, but different rules apply in permafrost regions. During the summer the top layer of the soil thaws. If plant parts fall on the thawed soil, they cannot be decomposed by microorganisms, because the soil freezes again before the microorganisms can finish their work. This means, that the carbon has not returned to the carbon cycle and has been trapped in the permafrost for thousands of years. Thus, active layers could be formed, some of them having a thickness of several hundred meters and store an extremely large amount of carbon. If this active layer melts due to climate change (see chapter 2.1) the underlying layers will also be destabilized and are likely to thaw. When this occurs, microorganisms will break down the carbon preserved in them and return it to the carbon cycle (Jacob, 2021).

This could turn the Arctic from a carbon sink to a carbon source of climate gases and accelerate climate change dramatically.

Other (local) consequences of warming in the boreal and subboreal Arctic are more frequent large-scale fires, erosion of earth masses, and also the disappearance of large areas of water. The thawing of permafrost also threatens the stability of cities, transport routes, pipelines and industrial plants (IPCC, 2022). The environmental disaster of Norilsk shows how strong the impact on the Arctic infrastructure is. A petrol depot of a thermal power plant, whose foundations were anchored in the permafrost cracked. As a result, over 20.000 tons of diesel were released into the environment (Jacob, 2021).

The global consequences of thawing permafrost are difficult to estimate, but the acceleration of climate change will have direct consequences for humankind and nature. These include an increase in extreme weather events, rising sea levels and a rise in temperature. This changing situation will then give rise to further challenges such as extreme weather events, heat stress, poor air quality, less clean water, reduced food security, increased spread of diseases, as well as unpredictable social consequences. The transgression of these ecological boundaries, also defined as planetary boundaries (see chapter 4), endangers the livelihood of humankind. (Haines & Ebi, 2019).

III. The Project: Pleistocene Park

The idea of the scientist Sergei Zimov is to create again an ecosystem as it was in the pleictocene. The area is located in eastern Siberia on the lower reaches of the Kolyma River south of the city Tchersky. He is convinced, that it is possible to reverse the shift of the last 10.000 years within the ecosystem (see chapter 2), to reduce the accelerated thawing of the permafrost soils. In order to achieve this, he wants to re-introduce large herbivores in significant numbers to restore the Arctic grasslands of the late Pleistocene.

The scientist has been pursuing this idea since 1988, when he began to introduce Yakutia horses to the area and observe their influence on the local ecosystem. Unfortunately, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, his project also came to an end, because all funding was cut off and he had to sell the horses. The project could only be resumed in 1996 and today covers more than 2000 hectares. Today, not only horses live in the park, through donations, other animal species could be settled in the area. These include reindeer, elk, musk oxen, bison, camels, wapiti and goats. For the next few years, there are also plans to settle the very rare and endangered Siberian tiger in the area (Viering, 2021; Windirsch et al., 2021).

In a TV-documentary Sergei Zimov, the head behind the project, even plays with the idea of resurrecting mammoths, he says: “Yes is need mammoths, I need 50.000 for the beginning but at the moment I can't get them anywhere […] I think the chances are good that it will happen because the elephants have survived until today and the genome of the mammoths is still contained in our permafrost and genetic engineering is making great progress. Also, it may not be necessary to bring a real mammoth back to life, but only to change the genetic characteristics of today's elephants, so that they can adapt to the cold climate (Lohr, 2017)”.

The underlying theory is that, grazing herbivores will massively transform the current landscape. This means that the ecosystem is changing from a bush and tree-rich tundra into a productive grassland. This will allow more herbivores to be fed in the future, which in turn will produce more excrement that will act as a natural fertilizer which makes the ecosystem more productive. The fact that the animals transform the current landscape into a steppe tundra makes it much brighter. This increases the albedo effect by about 10%. The reflected thermal energy can significantly slow down the thawing process (Macias-Fauria et al., 2020).

In winter, the large herds also fulfill another function: they compact the snow with their hooves. The snow then insulates much less and the frost can reach much further into the ground. This effect is not only theoretical but can be measured. Where the animals graze, temperatures of -20°C can be detected at a depth of 50 cm. Outside the park, without the animals, it is only -7°C degrees at the same depth.

The larger the herds and the larger the animals, the more powerful the effect becomes (therefore the mammoths). At the moment there are about 200 animals in the park but the target is tens of thousands (Macias-Fauria et al., 2020; Windirsch et al., 2021; Zimov, 2005).

By now, the park is not the solo project of Sergei Zimov and his son Nikita anymore. It is owned by a non-profit corporation, the Pleistocene Park Association, consisting of ecologists from the Northeast Science Station in Chersky and the Grassland Institute in Yakutsk. The reserve is surrounded by a 600 km² buffer zone, which will be added to the park by the regional government once the animals have successfully established themselves (Pleistocene Park, 2022).

IV. Planetary Boundaries

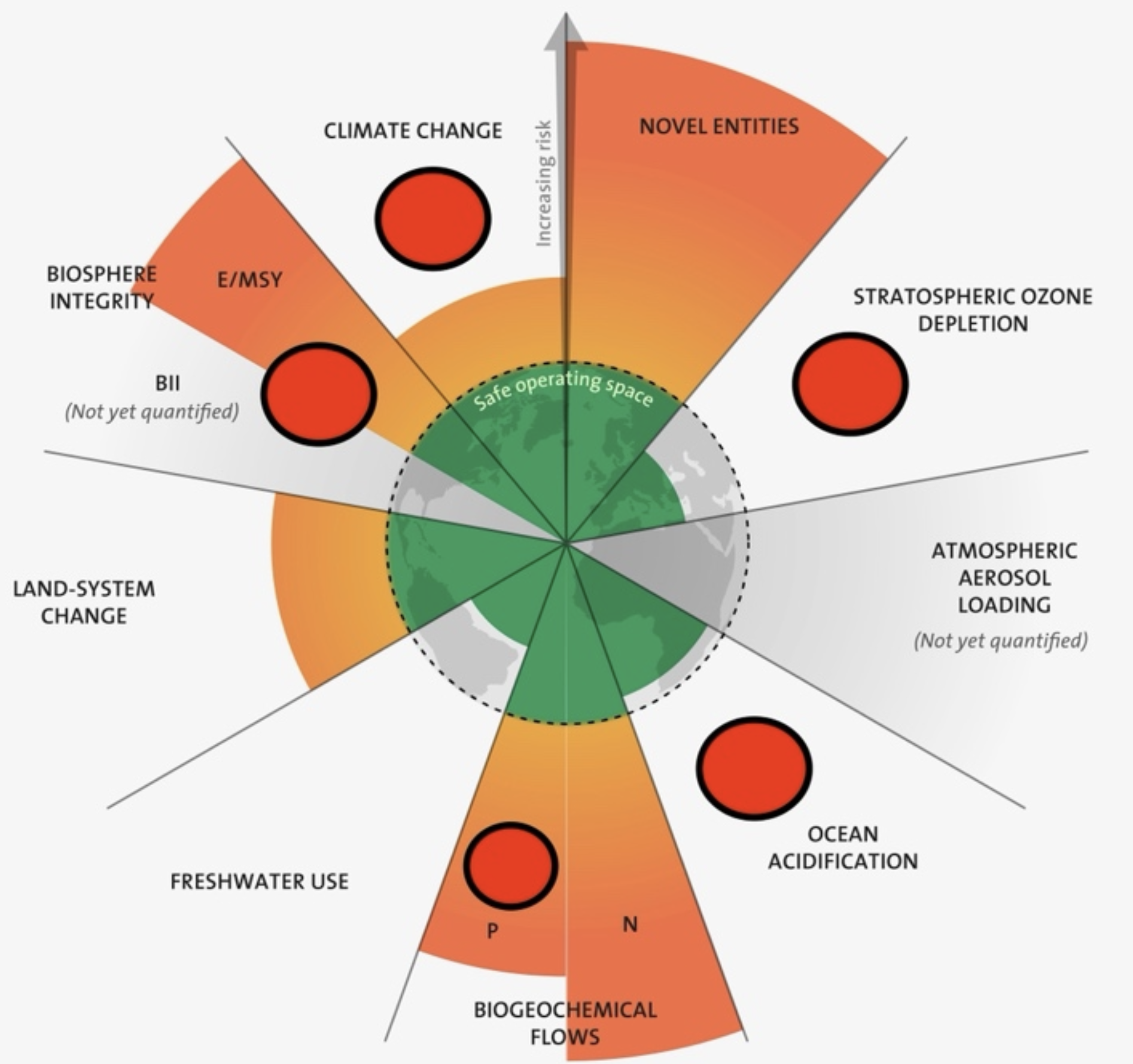

Figure 1 Own editing, based on: Planetary Boundaries (Stockholm Resilience Centre, 2022)

Figure 1 Own editing, based on: Planetary Boundaries (Stockholm Resilience Centre, 2022) To which part of the model is this project contributing?

The red dots in Figure 1 mark the areas which could be positively influenced by the renaturation of the Pleistocene Park. The concept of Planetary Boundaries (PB) is particularly well suited to depict the positive effects of the park's nature management strategy, because both, the project itself and the PB-Model have a global approach. For instance, one of the relevant research fields of the PB concept is; How small-scale regime shifts can propagate across scales and possibly lead to global-level transitions (Steffen et al., 2015)? Sergei Zimov and his team are trying to find an answer to this question in relation to the Pleistocene Park. So, what influence do sub-global dynamics in Siberia have on the global climate. Moreover, they try to find out to what extent the project can be scaled up to other areas (Viering, 2021; Windirsch et al., 2021).

The following explains why the park’s sub-global strategies play a critical and perhaps special role in adapting to global climate change:

Stratospheric Ozon Depletion:

The ozone layer filters ultraviolet light (UV) from solar radiation. This UV-light is particularly harmful to most living creatures on Earth, as it is DNA damaging and can cause cancer. Certain substances lead to the depletion of ozone in the stratosphere and thus to a reduction in the protective effect.

One of these substances is Nitrous oxide (N2O), which under certain circumstances can also be produced in significant quantities when the permafrost thaws. Nitrous oxide remains in the atmosphere for a very long time and therefore has long-term potential to damage the ozone layer, making it particularly important to act promptly, otherwise the damage is irreversible (Voigt et al., 2020).

The central idea behind the park is it to make the permafrost more resilient to global climate change and to slow or stop the thawing process of the soil. The initiative could be a leverage point to prevent the emission of nitrous oxide into the atmosphere and demonstrates the potential global relevance of the targeted objectives (see chapter 3).

Ocean Acidification:

The oceans are naturally slightly alkaline, but due to the increase of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere, the ocean is becoming increasingly acidic. This is due to the function of the sea as a natural carbon sink, but the increasing amount of CO2 in the atmosphere affects the healthy uptake capacity of the oceans.

Normally, the healthy pH-value of the sea is maintained by the balance of absorption and release of CO2, but this process is no longer in balance as a result of anthropogenic climate change. This is caused by a chemical reaction that produces carbonic acid (H2CO3) which has a lower pH-value and makes the oceans therefore more acidic. Cold-water areas are particularly at risk, since Carbon dioxide dissolves particularly well in cold water. This is why ocean acidification is progressing, especially in the polar regions (IPBES, 2019).

The consequences for the various ecosystems in the oceans are devastating. For example, many life forms that have calcium carbonate as a component, are unable to cope with increasing acidification. These include corals, zooplankton, phytoplankton, conches, red algae, sea urchins and calcareous algae etc.

These changes are upsetting the ecological balance of the oceans. This is evident in corals (reefs) for example. These ecosystems, which are particularly rich in species, suffer in some regions from living conditions that are too warm and too acidic. The change in pH results in too little carbonate available as a building component of the corals itself. With the consequence that the reefs cannot renew themselves or have very long growth phases.

This also has consequences for 400 million people who rely for their food and protection from storm waves to intact coral reefs (Aze et al., 2014).

There is only one effective way to combat ocean acidification: Greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) must be reduced. This includes slowing down the thawing of the permafrost (see Chapter 3), otherwise huge amounts of GHG, especially CO2, will be released, which would then have to be additionally absorbed by the oceans.

But even if we could stop all emissions overnight, the ocean would need thousands of years to fully recover (Aze et al., 2014; IPBES, 2019).

Biochemical Flows (Phosphorus):

About one-third of all the world's coasts are permafrost coasts, whose sediments had been frozen for millennia.This phenomenon can also be observed in the Pleistocene Park on the banks of the Kolyma River, which ends in the East Siberian Sea. As air temperatures rises, the coasts increasingly disintegrate as the permafrost thaws and the water continues to erode the now softened coasts. This not only produces GHGs, but also releases many nutrients, including phosphorus in the environment.

This nutrient input leads to fertilization of the oceans and increases the primary production, i.e., the biomass in the sea is increases by plants, algae and bacteria. This happens mainly in the upper, warmer water layers with a high solar radiation. From the resulting turbidity of the water, the underlying water layers receive less sunlight, which leads to a diminished photosynthesis and therefore an overall reduced amount of phytoplankton. The release of phosphorus (and other substances from the permafrost), changes the living conditions in the coastal zones with long-lasting consequences The consequences for the food web can only be guessed and are not yet foreseeable and require further research (Fritz et al., 2017).

More certain knowledge exists in the context that a reduced number of phytoplankton is problematic because it provides food for zooplankton and fish. In addition, phytoplankton are also called “trees of the sea”. This shows how important it is for the global climate. It plays a key role in the global carbon cycle (biological carbon pump)(Neuer et al., 2014).

The project of Sergei Zimov and his team can also make a contribution here, to keep the permafrost banks stable and preventing a further negative impact on the biochemical phosphorus flow. How he wants to implement this is described in chapter three of this paper.

Biosphere Integrity:

Biosphere Integrity (and Climate Change) are defined as Core boundary of the model, based on their fundamental importance for the Earths system (ES) (Steffen et al., 2015).

Biodiversity forms the basis for the entire biosphere and therefore its integrity. Biodiversity is a key component of the Earth system. It is essential for the existence of humanity. However, humans are currently causing losses in the biodiversity of the earth, which are quite similar to the mass extinction events known from the history of the earth (see chapter 2). Many consequences of the progressive loss of biodiversity are already seen in an increasing vulnerability of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, changes in climate and ocean acidity (see chapter 4, Ocean acidity). The mentioned extinction rate exceeds the rate of speciation by far. The average extinction rate for marine organisms and mammals in the fossil record is 0.1 to 1 extinction per million species-years (E/MSY). Since the beginning of the Anthropocene, humans have increased the rate of species extinction by 100 to 1000 times compared to the background rates common in Earth history, resulting in a current average global extinction rate of ≥100 E/MSY. This greatly accelerated rate of species loss severely threatens the viability of ecosystems and it is questionable if their functioning can be sustained under these new conditions. Especially, the loss of top predators and structurally important species such as corals and kelp forests have a major impact on ecosystem dynamics. (Rockström et al., 2009)

These tipping points are caused and accelerated by global climate change. The problem with these tipping points is that they are irreversible and have severe global and sub-global consequences in the interconnected and interdependent biosphere. Research shows that at an average global warming of 2°C, the extinction rate will increase from the current 2,8% to 5,2%. In a scenario where average temperatures would rise by 4°C, which is more likely, the risk of extinction would increase to 16% (Drenckhahn et al., 2020).

These figures show how crucial the CO2 level in the atmosphere is and that average temperatures should not rise any further. Reducing emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases is therefore essential.

The Pleistocene Park, which aims to reduce GHG emissions in order to slow down climate change and avoid critical tipping points and thereby positive feedback loops, is a good example of how this can be done. It is precisely this loss of biodiversity and its consequences on a local and global level that the park is trying to counteract by introducing mammals, which will decisively increase biodiversity (see Chapter 3).

Climate Change:

Climate Change (and Biosphere Integrity) are defined as Core boundary of the model based on their fundamental importance for the Earths system (ES) (Steffen et al., 2015).

Climate change can be observed throughout the biosphere. Among the most important observations of climate change are the rapid decline of sea ice in the Arctic, the retreat of mountain glaciers around the world, the loss of mass of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, the increased rise of sea levels in the last 10 to 15 years and the shift of subtropical regions 4°pole wards. Furthermore, it is seeable in increased bleaching and mortality in coral reefs, an increase in large floods, and the activation of slow feedback processes such as the weakening of the oceanic carbon sink (Rockström et al., 2009).

This is due to the anthropogenic greenhouse effect, whose emissions come from all areas of the planetary boundaries model. For all these areas, there are clear reduction targets to mitigate the synergies between biodiversity loss and GHG emissions.

Previous research shows that the park could make an important contribution by allowing frost to penetrate deeper into the ground, boosting photosynthesis to capture more CO2 from the air, and greatly increasing the albedo effect. The methane (CH4) emissions of the animals are always the subject of discussion. While it is true that the animals emit a certain amount of methane each year, they contribute to halving the total methane emissions from the park's landscape. The them improve the soil water balance through direct grazing and less methane escapes. The amount of CH4 emitted by the animals is very insignificant compared to the amount saved (Beer et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Sergei and his son Nikita share the view that only nature can save humankind. They are not worried about animals, which will always survive. Nikita Zimov is more concerned about his children and wants them to live on a better planet. That's why they created the Pleistocene Park, simply because it is necessary to survive on the earth in the future. They are urgently looking for reinforcements for their mission, so that the project could have long-term success (Lohr, 2017).

If they get this reinforcement, the chances are good to really make a change, because if scaling up the project becomes possible and large herbivores can be introduced throughout the Arctic to graze at a similar density as in the Pleistocene Park, this would have a significant effect simply by trampling the insulating snowpack: the ground would warm by only 2°C. That is theoretically enough to preserve 80 percent of the permafrost that exists today (Beer et al., 2020)!

Recommended video

https://www.arte.tv/en/videos/078777-000-A/arte-reportage/References

- Aze, T., Barry, J., Bellerby, R., & Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2014). An updated synthesis of the impacts of ocean acidification on marine biodiversity. http://www.deslibris.ca/ID/244312

- Beer, C., Zimov, N., Olofsson, J., Porada, P., & Zimov, S. (2020). Protection of Permafrost Soils from Thawing by Increasing Herbivore Density. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 4170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60938-y

- Brook, B. W., & Bowman, D. M. J. S. (2002). Explaining the Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions: Models, chronologies, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(23), 14624–14627. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.232126899

- Drenckhahn, D., Arneth, A., Filser, J., Haberl, H., Hansjürgens, B., Herrmann, B., Homeier, J., Leuschner, C., Mosbrugger, V., Reusch, T. B. H., Schäffer, A., Scherer-Lorenzen, M., & Tockner, K. (2020). Globale Biodiversität in der Krise: Was können Deutschland und die EU dagegen tun? = Global biodiversity in crisis: what can Germany and the EU do about it? (H. Steinicke, Ed.). Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina e.V. - Nationale Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Fritz, M., Vonk, J. E., & Lantuit, H. (2017). Collapsing Arctic coastlines. Nature Climate Change, 7(1), 6–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3188

- Haines, A., & Ebi, K. (2019). The Imperative for Climate Action to Protect Health. New England Journal of Medicine, 380(3), 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1807873

- IPBES. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5657041

- IPCC. (2022). The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964

- Jacob, K. (2021). Max Planck Forschung. 88.

- Lohr, B. (Director). (2017). ARTE Reportage - Siberia: The Melting Permafrost - Watch the full documentary. https://www.arte.tv/en/videos/078777-000-A/arte-reportage/

- Lucas, Z., & Enos, J. (2019). Modeling the Impact of the Pleistocene Park with System Dynamics. New York, 8.

- Lundgren, E. J., Ramp, D., Rowan, J., Middleton, O., Schowanek, S. D., Sanisidro, O., Carroll, S. P., Davis, M., Sandom, C. J., Svenning, J.-C., & Wallach, A. D. (2020). Introduced herbivores restore Late Pleistocene ecological functions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(14), 7871–7878. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1915769117

- Macias-Fauria, M., Jepson, P., Zimov, N., & Malhi, Y. (2020). Pleistocene Arctic megafaunal ecological engineering as a natural climate solution? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375(1794), 20190122. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0122

- Miner, K. R., Turetsky, M. R., Malina, E., Bartsch, A., Tamminen, J., McGuire, A. D., Fix, A., Sweeney, C., Elder, C. D., & Miller, C. E. (2022). Permafrost carbon emissions in a changing Arctic. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 3(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00230-3

- Neuer, S., Iversen, M., & Fischer, G. (2014). The Ocean’s Biological Carbon pump as part of the global Carbon Cycle. Limnology and Oceanography E-Lectures, 4(4), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.4319/lol.2014.sneuer.miversen.gfischer.9

- Pleistocene Park. (2022, May 8). https://pleistocenepark.ru/

- Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, A., Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E., Lenton, T. M., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schellnhuber, H. J., Nykvist, B., Wit, C. A. de, Hughes, T., Leeuw, S. van der, Rodhe, H., Sörlin, S., Snyder, P. K., Costanza, R., Svedin, U., … Foley, J. (2009). Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society. 14(2): 32, 14(2). http://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/39052

- Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., Biggs, R., Carpenter, S. R., de Vries, W., de Wit, C. A., Folke, C., Gerten, D., Heinke, J., Mace, G. M., Persson, L. M., Ramanathan, V., Reyers, B., & Sörlin, S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347(6223), 1259855. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855

- Stockholm Resilience Centre. (2022). https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

- Viering, K. (2021, July 29). Renaturierung: Zurück in die Eiszeit. https://www.spektrum.de/news/renaturierung-zurueck-in-die-eiszeit/1899424

- Voigt, C., Marushchak, M. E., Abbott, B. W., Biasi, C., Elberling, B., Siciliano, S. D., Sonnentag, O., Stewart, K. J., Yang, Y., & Martikainen, P. J. (2020). Nitrous oxide emissions from permafrost-affected soils. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1(8), 420–434. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0063-9

- Windirsch, T., Grosse, G., Ulrich, M., Forbes, B. C., Göckede, M., Wolter, J., Macias-Fauria, M., Olofsson, J., Zimov, N., & Strauss, J. (2021). Large Herbivores Affecting Permafrost – Impacts of Grazing on Permafrost Soil Carbon Storage in Northeastern Siberia [Preprint]. Biogeochemistry: Soils. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-2021-227

- Zimov, S. A. (2005). Pleistocene Park: Return of the Mammoth’s Ecosystem. Science, 308(5723), 796–798. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1113442