The economy for the common good

An economic model for the future

Updated at 31.08.2022

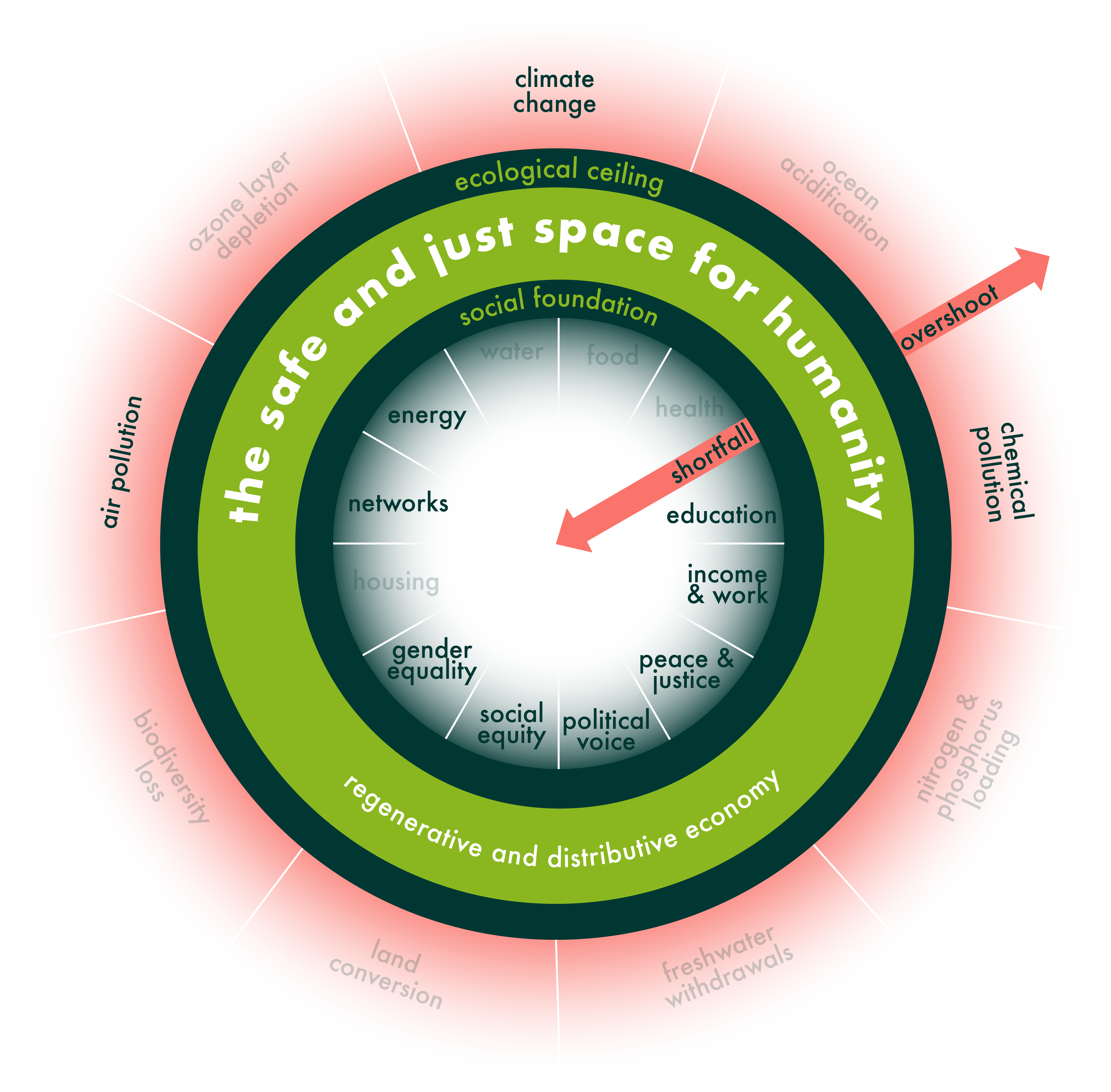

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subject

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subjectI. Introduction

Given the impending climate catastrophe and the prevailing enormous social inequalities, the question arises as to how we can still avert it. For this, it is enormously important to create a turnaround in every single area, both in the industry - especially the energy production for it - and in nature conservation (IPCC, 2022).

Nevertheless, the question also arises, what is the core of our current problems? Is there a certain origin for the exploitation of both humans and nature? With these considerations, one does not come past the topic of the prevailing value and economic systems. Capitalism and the accompanying greed for profit and self-enrichment – without regulations - inevitably lead to this exploitation. Today's economists see the sense of economic activity only in the increase of profit and less in the creation of added value for society (Felber & Maskin, 2015). Capitalism is based on being as effective as possible through a free market and the competition that prevails, thus bringing progress and prosperity to all (Smith, 2016). But with which justification and on what scientific basis is this assumed? Today's studies show that competition is indeed a good driver of progress and motivates people. However, it is not the best and it inevitably leads to profit and progress at the expense of other people or companies. This can also be seen in the widening gap between rich and poor (Keeley, 2015). What drives people even more than competition is to see meaning in their actions, to do something important and meaningful for themselves, the people who are around them and in the optimal case even for all people in this world. The values represented in capitalism contrast with the values adopted for a happy life of people in social life in disciplines such as psychology. For social well-being and a fulfilled life, values such as trust, honesty, respect, empathy, mutual help, appreciation, and cooperation are central, whereas capitalism with its systematic pursuit of profit and competition leads to selfishness, greed, envy, ruthlessness and irresponsibility (Felber & Maskin, 2015; Thane S. Pittman & Kate R. Zeigler, 2007). Now one could go even further and question where this economic system comes from again, is it based on the nature of humans and is it natural and given or a "trained" and brought up behavior, which is passed on by school and past life from generation to generation? Couldn't this learning and training lead to a sustainable change through a different value and, in consequence, economic system, which is not based on self-enrichment and endless growth and thus lead society away from the ruthless exploitation of nature? Given these considerations, the "degrowth" debate has been going on for many years, calling for a turn away from endless economic growth (Kallis et al., 2018). This turning away is based, above all, on studies according to which humans gain no further exponential increase in life satisfaction starting from a certain measure of prosperity and thus making an endless growth redundant (Lucas & Schimmack, 2009).

Based on these considerations, the movement of the economy for the common good was formed, which aims to promote a rethinking of economic activity. In the economy for the common good, the goal of companies should no longer be the optimization of profits, but rather to focus on the added value for the common good of society. On closer inspection and a look at various constitutions, it is precisely this common good that should originally be the focus of economic actions (Felber, 2021).

II. What is the economy for the common good (ECG)?

The economy for the common good is a civil society movement which was founded in 2010 by Christian Felber – an Austrian author and political activist - in Austria. From there, the ECG initially spread throughout the German-speaking world. In the meantime, however, it can also be found in the Benelux countries, Scandinavia and Eastern Europe, as well as in South America, the USA and Canada, where the first local chapters have already joined forces. The ECG wants to force an impact on three levels: Influence in politics to change the economic system, transform economic companies, organizations and municipalities and create awareness in the civil society. To reach this, the economy for the common good organizes itself through registered associations, which unite then again under their roof local chapters and hubs. In those local chapters and hubs, engaged and interested ones can join the ECG movement and actively participate. To join the local chapters, there are no requirements and they are responsible to spread the idea by planning and organizing local events to raise awareness and connect to different companies, municipalities and organizations to expand the network, while the hubs are more specific working groups, with topics such as the auditor hub or consulting hub, which also includes (economic-) professionals. For now, the ECG has already more than 4.285 Members, 173 local chapters and 44 Municipalities involved. More than 2000 companies actively support the ECG, of which about 500 are members or have already been certified. Among the companies are well-known global players such as "Vaude", "Sonnentor" or the "Sparda Bank Munich" (Economy for the common good, 2022f; Felber, 2021; Felber & Maskin, 2015).

III. Idea and concept of the economy for the common good

In today's economy, the degree of the success of enterprises is measured only by their conversion and profit. Even on a national level, the Gross domestic product (GDP) is considered the gold standard to measure the "state" of a country, but this is not the only and right measurement for wealth and success (Haberl et al., 2020; van Bergh, 2009). The goal of the economy for the common good is to create a common good society and therefore change the economic system and shift the focus of companies from accumulating money and capital to the common good, which is the original purpose of economic activity and is stated in many constitutions (Felber, 2021). “A common good society allows all people

- to interact with each other with tolerance and mutual respect for diversity and diverse lifestyles

- define their personal values, set their individual goals, find their identity and develop their full potential

- develop their talents and skills and, in this way, help them contribute to the Common Good in a meaningful and cooperative manner

- actively engage in politics, making democratic decisions and thus helping shape our future” (Economy for the common good, 2022g).

To force this shift and to make sure the economy serves the common good, the ECG created, on the one hand, the common good product and on the other hand the common good balance sheet for companies and municipalities (Economy for the common good, 2022g; Felber, 2021; Felber & Maskin, 2015).

Common good product (CGP)

“The common good product (CGP) is an economic instrument that measures the achievement of core values of a society and progress made towards economic goals derived from these values” (Economy for the common good, 2022c). The CGP aims to replace the GDP to create a more sustainable and social society and state. Since participation plays an important role in the economy for the common good movement, the idea to build up the CGP and therefore the societal goals and measurement of the success of a country is realised by a citizens´ assembly, where people can propose the most relevant areas to be measured for the quality of life, well-being for all and the common good. Out of those proposals, 20 areas will then be chosen for building up the CGP. For now, this idea is not applied but is rather a proposal for western countries in recognition of other already implemented measurements and indexes such as “Buthan´s Gross National Happiness Index” (Alkire, 2008; Economy for the common good, 2022c; Felber, 2021).

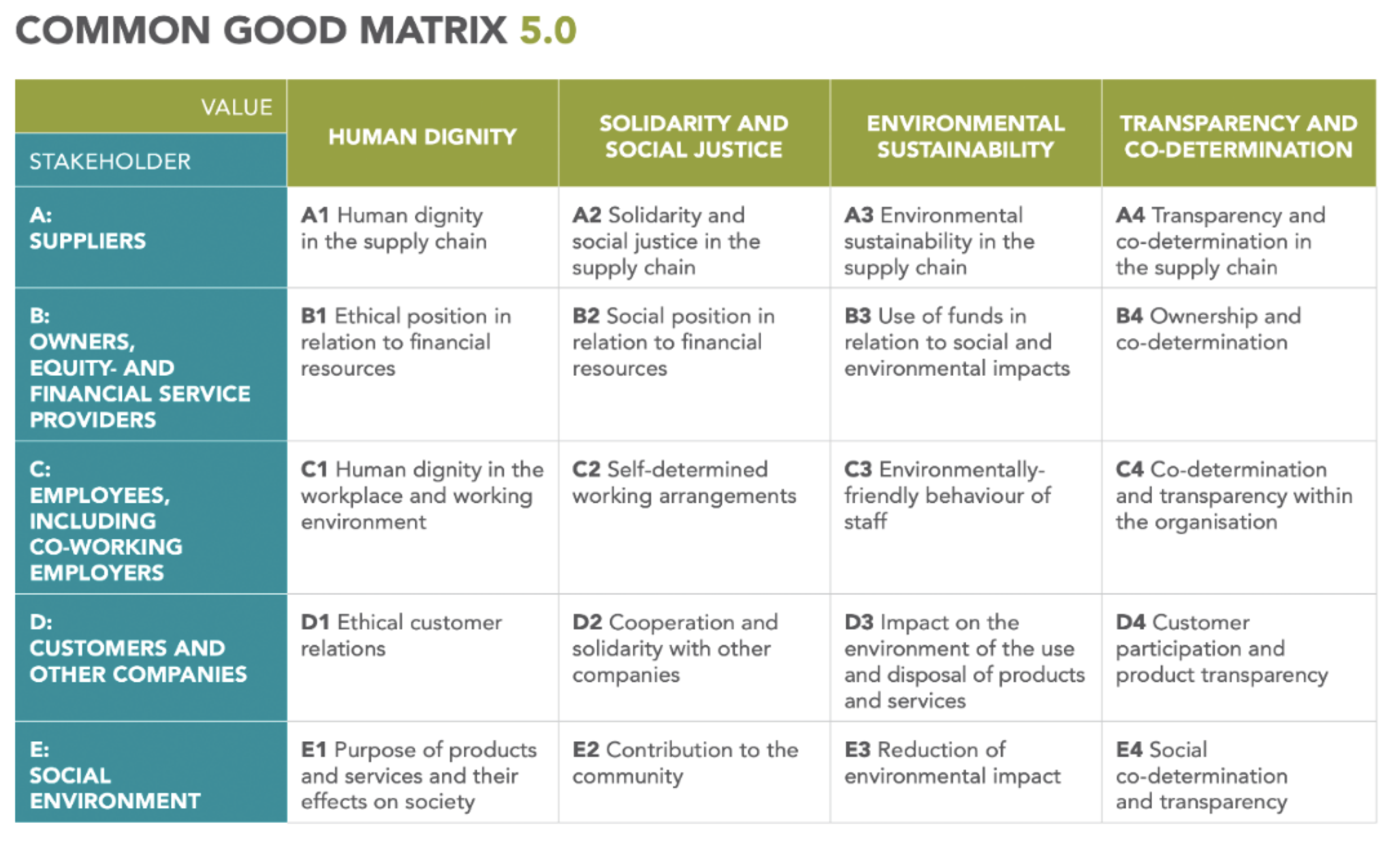

Common good balance sheet and the common good matrix

The “common good balance sheet” aims to measure the contribution of companies, organizations and municipalities to the common good and rates how they are acting in the presence and how they can improve in the future, thus making it transparent for everyone. For the preparation of a common good balance sheet, it is first of great importance to define the common good more precisely and to determine which parameters are to be used to measure it. To accomplish this, the economy for the common good movement has created a common good matrix (Figure 1), which is the base for the common good balance sheet and is constantly being developed further.

The core values of the common good matrix are human dignity, solidarity and justice, environmental sustainability, and transparency and co-decision. These are then applied to all levels of the rated company, organization or municipality. This includes suppliers, owners and financial partners, employees, customers and fellow companies and the social environment. The intersection of the values and the "target groups" then results in a total of 20 common good topics. These 20 topics are then evaluated individually and possible potentials and targets are also revealed. The evaluations of the individual topics are then determined in an overall evaluation in the form of a common good score. A maximum of 1000 common good points can be achieved, and up to a maximum of 3600 minus points can also be awarded for practices that are detrimental to the common good. The common good balance sheet claims to be applicable to companies and organizations of any sector, size and legal form. Only the weighting of the various topics is adjusted according to the size, financial flows, social risks and the industry of the company, whereby the achievable total remains the same. The common good balance sheet is in the first place done by the company itself by gathering all kinds of relevant documents and evidences. Afterwards, the balance sheet gets checked and evaluated by professional management consultants, who are certified by the ECG. They also offer consulting and help in the creation phase of the common good balance sheet.

Fig.1. Common Good Matrix 5.0 (Economy for the common good, 2022b)

Fig.1. Common Good Matrix 5.0 (Economy for the common good, 2022b)The future vision of the ECG is that common good accounting will become mandatory for all companies and thus represent an extension of the non-financial accounting already enshrined in EU law in 2017, which approximately will already be extended by the end of this year (Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Ausschusses für Recht und Verbraucherschutz (6. Ausschuss), 2017; PWC, 2021). If this is the case, the next step would be that companies and institutions with a high overall rating in the economic system are treated preferentially - for example through tax relief and subsidies - to create an incentive to align economic activity with the common good. This would counteract the problem that companies are at a disadvantage in today's marketplace by investing in more sustainable and equitable actions. Aligning with the common good also has the advantage that companies no longer act on their own and view other companies as competitors, but rather a cooperative action between companies is promoted and problems can thus be worked on together.

In addition to rating companies, the common good economy also sees its task in educational work. Thus, the concept should also find its way into schools and educational institutions. The concept of the economy for the common good should be and is already taught at universities in the form of project workshops, seminars and even the first master's study program “applied economy for the common good”, which was found at the University of Applied Sciences Burgenland (Economy for the common good, 2022a), and thus sensitizes tomorrow's managers to these issues and promotes change, especially in business-related study courses (Economy for the common good, 2022f; Felber, 2021; Felber & Maskin, 2015).

IV. Leverage points in the Doughnut Economy

The claim to align the economic actions of companies and organizations with the common good correlates strongly with the claim of the doughnut economy and thus has an effect - albeit often indirect - on many levels and aspects of it. They both have the aim to create a thriving society in the existing planetary boundaries, but the doughnut economy is still an overarching concept and framework, while the economy for the common good provides concrete tools to change the economic system (Felber, 2021; Raworth, 2017).

By balancing and aligning with the common good, which according to the definition of the ECG is oriented towards the values of human dignity, solidarity and social justice, ecological sustainability and transparency and co-decision-making, it leads to companies and organizations wanting to improve on these levels and - especially in the case of subsidies for positive behaviors - also been given the chance implementing actions to reach this improvement. Thus, in the context of Planetary Boundaries, different aspects are addressed depending on the type and sector of the company. Since the ECG refers in first place to economic enterprises, here above all climate change, chemical pollution and air pollution are addressed, since these represent for many enterprises the main affected issues in production processes (Felber & Maskin, 2015; Raworth, 2017).

In the context of the social foundations, the economy for the common good addresses many aspects as well. Considering the disclosure through the common good balance sheet regarding Human Dignity and Solidarity and Social Justice both within the company and in the supply chains, a more just and social treatment is promoted and thus contributes to the aspects of income and work, social equity and gender equality of the doughnut economy. With a possible obligation by the legislator, these can be increased even further, since it becomes evident for each enterprise how you behave in these topics, and the final consumer prefers - in the best-case – enterprises which align themselves on it (Felber & Maskin, 2015). By the different multiplicators and local chapters, the range of education is also included. Just the spreading in schools and universities of these topics leads to better education and an improved social living with each other, even if it is not guaranteed that people who do not have access to education yet are included. Through an increased awareness in society and thus an increased cooperative behavior and reflection on values that stand for a happy and fulfilled life, the sphere of Peace and Justice of the Doughnut Economy will then also be addressed (Felber, 2021; Felber & Maskin, 2015; Raworth, 2017).

V. Successes and conclusion

The economy for the common good is a steadily growing movement, which - with its idea and vision - is already making an important contribution to changing the economy and can continue to do so. Many companies, organizations and municipalities have already joined the movement and it is also gaining more and more support in politics. It has already been recognized by the EU Commission and is supported by further research (Economy for the common good, 2022e; Opinion of the Economic and Social Committee on ‘The Economy for the Common Good: a sustainable economic model geared towards social cohesion’, 2016). The openness of the movement, without claiming to be the only right concept to create and implement change in the economic system but one of several tools and concepts from which the best aspects should be taken together, generates a great potential to develop it further. This has led to the ECG joining the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) earlier this year, along with 12 other organizations and movements. The EFRAG is responsible for the revision of the EU's Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and thus has a decisive influence on future legislation within the EU framework (European Financial Reporting Advisory Group, 2022). Thus, the ECG will be an active contributor to this revision and has a decisive influence on the legislation at EU level.

On a regional level as well, more and more municipalities and regions all over the world are becoming common good municipalities and regions and are integrating the concept of the economy for the common good into their constitutions, such as Alto Adige, Italy; Miranda de Azán, Spain; Mäder, Austria; Kirchanschöring, Germany or the region of Höxter, Germany (Economy for the common good, 2022d). Therefore, the network and impact on both international and national levels increases. Nevertheless, there is still a long way to go before these measures are reflected in terms of benefits and competitive advantages in the “free market”. The voluntary nature of the scheme to date and the small gains in benefits for participating companies, organizations and communities through improved positive visibility and advantage through cooperation makes it a difficult undertaking to get large commercial enterprises on board (Valentin, 2019). Howbeit, the growing number of participants shows the desire in society to drive change in the economic system, and as the community grows, the pressure on politicians to support this change increases. Thus, the economy for the common good is on a promising path and its work is already paying off. In the end, the concept and the vision of the ECG is promising by tackling a fundamental root cause of today's problems and therefore has an impact on multidimensional layers, is worth supporting and can create change on a large scale.

References

- Alkire, S. (2008). Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index : Methodology and results. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI). https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:fe52b6a2-94c7-4663-89aa-d09c19d32ab8

- Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Ausschusses für Recht und Verbraucherschutz (6. Ausschuss), March 8, 2017. https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/18/114/1811450.pdf

- Economy for the common good. (2022a). Bildungsangebot. https://austria.ecogood.org/bildung/

- Economy for the common good. (2022b). Common Good Matrix. https://www.ecogood.org/apply-ecg/common-good-matrix/

- Economy for the common good. (2022c). common good product. https://www.ecogood.org/apply-ecg/common-good-product/

- Economy for the common good. (2022d). Municipalities. https://www.ecogood.org/apply-ecg/municipalities/

- Economy for the common good. (2022e). Political Impact and Initiatives. https://www.ecogood.org/what-is-ecg/political-impact-and-initiatives/

- Economy for the common good. (2022f). Vision and Values. https://www.ecogood.org/what-is-ecg/vision-and-values/

- Economy for the common good. (2022g). Vision and Values. https://www.ecogood.org/what-is-ecg/vision-and-values/

- Opinion of the Economic and Social Committee on ‘The Economy for the Common Good: a sustainable economic model geared towards social cohesion’, Official Journal of the European Union (2016). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015IE2060&from=DE

- European Financial Reporting Advisory Group. (2022, January 25). Milestones in EFRAG´s governance reform: The EFRAG General Assembly has approved the admission of thirteen new EFRAG Member Organisations and the revised EFRAG Statutes and Internal Rules [Press release]. Brussels. https://www.efrag.org/Assets/Download?assetUrl=/sites/webpublishing/SiteAssets/press+release+milestones+sustainability+reporting+25+01+22.pdf&AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

- Felber, C. (2021). Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie (Komplett aktualisierte und erweiterte Ausgabe, 6. Auflage). Piper.

- Felber, C., & Maskin, E. (2015). Change everything: Creating an economy for the common good ((S. Nurmi, Trans.)). Zed Books.

- Haberl, H., Wiedenhofer, D., Virág, D., Kalt, G., Plank, B., Brockway, P., Fishman, T., Hausknost, D., Krausmann, F., Leon-Gruchalski, B., Mayer, A., Pichler, M., Schaffartzik, A., Sousa, T., Streeck, J., & Creutzig, F. (2020). A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: Synthesizing the insights. Environmental Research Letters, 15(6), 65003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a

- IPCC. (2022). Climate Change 2022 Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Summary for Policymakers.

- Kallis, G., Kostakis, V., Lange, S., Muraca, B., Paulson, S., & Schmelzer, M. (2018). Research On Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 43(1), 291–316. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-025941

- Keeley, B. (2015). Income inequality: The gap between rich and poor. OECD insights. OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264246010-en

- Lucas, R. E., & Schimmack, U. (2009). Income and well-being: How big is the gap between the rich and the poor? Journal of Research in Personality, 43(1), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.09.004

- PWC. (2021). Sustainability reporting enters a new era: Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive. https://www.pwc.ie/services/audit-assurance/insights/corporate-sustainability-reporting-directive.html

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st century economist. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Smith, A. (2016). The Wealth of Nations. Coterie Classics. Xist Publishing.

- Thane S. Pittman, & Kate R. Zeigler. (2007). Basic human needs (Vol. 1). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/thane-pittman/publication/232598005_basic_human_needs

- Valentin, S. (2019). The Economy for the Common Good and Its Enemies. The Different Positions of Proponents and Critics of the ECG-Propositions. https://api.pageplace.de/preview/dt0400.9783346022134_a39112450/preview-9783346022134_a39112450.pdf

- Van Bergh, J. C. den (2009). The GDP paradox. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(2), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2008.12.001