The city of change: a journey into the urban agriculture revolution in Berlin

Updated at 24.08.2022

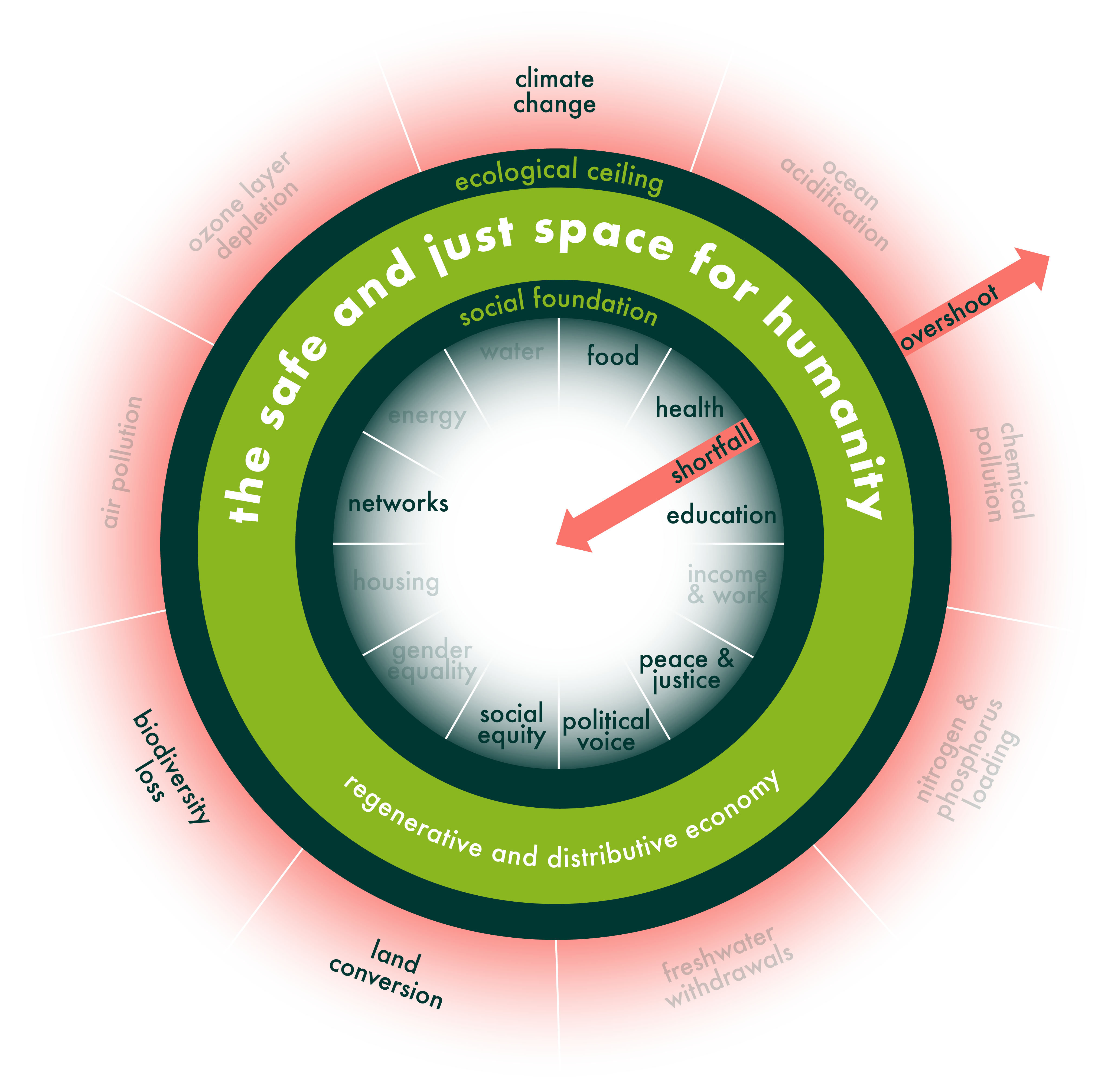

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subject

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subjectI. Introduction

Berlin's complex history has resulted in many vacant lots, allowing several urban agriculture-related projects to become part of the city's urban development. History plays a fundamental role in the development of these projects, from the bombings that the city suffered under during the Second World War, the Berlin Wall, and the division of the city to the crisis of deindustrialization that the city suffered after the fall of the Berlin Wall, contributing to the fact that many urban spaces were abandoned and used by civil society to create a new meaning and use to these forgotten spaces (Clausen, 2015). In December 2019, the Berlin Senate recognized the climate emergency humanity is facing. In order to get out of this environmental crisis, the urban sector has to find a way to develop without overstepping the planetary boundaries, as today around 56% of the world's population lives in cities (Karge,2021). The transition to the solution must include changing the current system of food production and consumption and conventional agriculture. What is thought to be normal today is not normal at all; mineral fertilizers, pesticides, massive monocultures, degraded soils, loss of organic matter, and heavy machinery (Clausen, 2015).

The chain of food production has been so aggressive towards different ecosystems and social systems, to the extent that human beings separate themselves from a life close to nature, managing to polarize themselves from the natural cycle of life. Microorganisms, plants and animals all are part of the cycle of life. Maintaining a suitable balance, they live a naturally regulated existence. People in the urban sector can see this world as a model of the strong consuming the weak or as a world of coexistence and mutual benefit. One or the other, it is an arbitrary interpretation causing disorder and confusion among many people (Fukuoka, 1978). Within the city of Berlin, there is much willingness to emerge, regenerate, and be reborn in balanced environments. But there is also frustration, that despite efforts such as recycling, cycling, and awareness of both material and food consumption, there are still many problems within the city. Because of these real frustrations, it is necessary to find solutions with more sense within the city since the city is full of proposals for nature to again take an important role in the search for balance. This contribution tries to show how some urban agriculture projects in Berlin are building a path in which nature takes the main protagonist role and humans are just part of a cycle, and will focus on describing the dense variety of possibilities of what a community garden within Berlin looks like and how to promote the use of spaces in Berlin in a way that the urban spaces are used in a functional and holistic way. Being “Doughnut Economics” being the overall topic of this compendium, here we will explain how urban gardening, urban agriculture, and community gardens in Berlin can make a relevant contribution to the concept in order to achieve an environmentally safe and socially just space in which the people of Berlin can thrive.

Every year in Berlin new projects related to urban gardening and community gardens are born. These initiatives, usually driven by civil society, are creating a new way of thinking and interaction in the city. Each of these projects represents a micro-universe of possibilities within a metropolis like Berlin. Beyond gardening, these projects stand out for their variety of activities such as soil care workshops, beekeeping, permaculture, composting, recycling, awareness of food consumption, etc. What these urban spaces have in common, along with the idea of focusing on local food production, is that they are community-initiated projects (Urban gardening manifest, 2022).

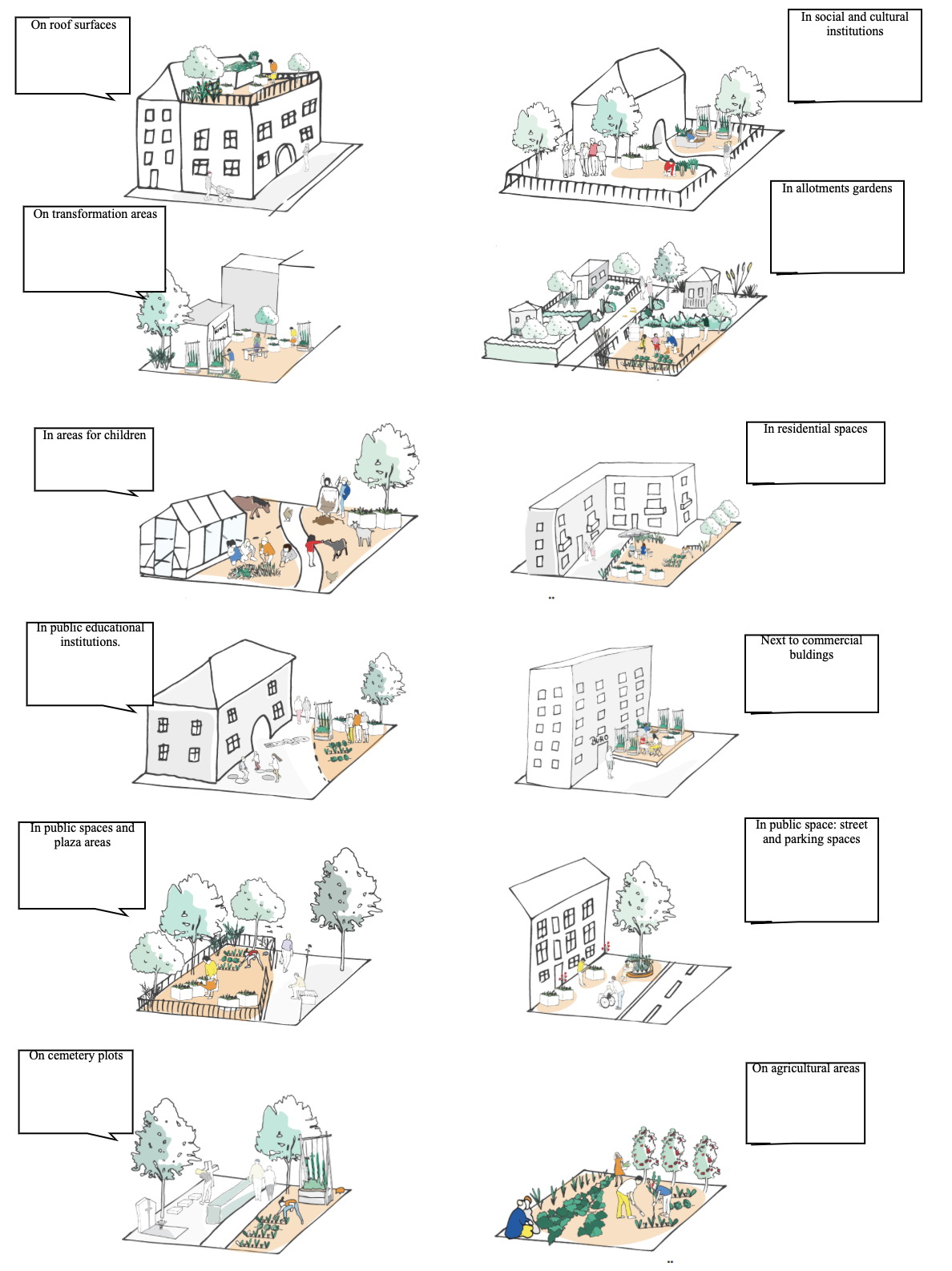

Berlin's community gardens are located in street spaces and parks, on squares and rooftops, in courtyards, or they are part of agricultural areas and spaces used by children. Community gardeners want to use these urban open spaces not only for growing vegetables and fruit, but they are much more concerned with the desire to become active collectively, initiate encounters to strengthen local cycles, politicize people and shape a place in the city according to their own ideas. In this way, they contribute not only to urban food production but also to biodiversity and climate adaptation, promoting the urban coexistence of people, animals, and plants (Karge 2021). According to the “Senatverwaltung für Umwelt, Mobilität, Verbraucher-und Klimaschütz” (SenUMVK) there are more than 200 community gardens in Berlin, which are practicing either urban gardening or urban agriculture. In Berlin, there are 12 different kinds of community gardens, each of these gardens has its own special features, and they vary in the types of areas where they are located. The community gardens in Berlin have a form of organization and differences in approaches to ecological, social, economic, or spatial context (Karge, 2021). There exists also a difference in the relationship to the surrounding urban space, accessibility, and possible conflict potentials. Organization methodology differs also in each project, some are more inclusive, and other projects are more focused on the cause of having a positive neighborhood. The goal of this small journey through the urban gardening world in Berlin is to see the dense diversity of projects in Berlin, which could help the city to be a better place to live in.

II. Types of community gardens in Berlin

Fig.1. The following 12 illustrations were extracted from Karge, T (2021). )

Fig.1. The following 12 illustrations were extracted from Karge, T (2021). )Gardening in roof spaces is becoming popular since most people don't have the possibility to have a green space in the city. The gardening activities on the rooftop could be diverse and range from growing vegetables and other plants to supporting bee colonies. Rooftop gardens are especially suitable for bees since they are on a similar level to the crown of trees so bees are able to find a quiet place to rest before flying back to the hive. Planted roofs also provide a better climate by reducing the inner-city heat effect and protecting the sewer system during heavy rainfall by retaining rainwater. Example: A roof garden can be found in the Neukölln Arkaden shopping mall, located in one of the most frequented streets in Neukölln, the Karl-Marx-Straße. The community garden “KlunkerGarten” offers freely accessible raised beds. Community gardens next to social and cultural institutions are created as extended places of gathering, exchange, and community strengthening within the respective association (e.g church, refuge shelters), often with the aim of opening up to and further involving the surrounding neighborhood. Social clubs and agencies integrate community gardening as an extended space for knowledge exchange. Example: The „Interkulturelle Garten für alle” located in Spandau next to the emergency shelter “Schmidt-Knobelsdorf-Kaserne” offers the people who were temporarily staying in the shelter to use the garden of the garden as a space to exchange experiences and knowledge. The garden works as a space where people from the neighborhood could get in touch with persons who are in vulnerable situations (Karge, 2021).

Gardens located in spaces in transformation are located on unused land. These spaces usually are owned by private stakeholders or by the city. Here, building plots are intended and as long as the construction of a possible building has not started, people start gardening projects on the land until they are allowed to do so. The unsecured legal situation of garden use on private property, from temporary tolerated use to eviction when the property is sold, plays an important role. Example: The “Prachttomaten” in Neukölln has achieved to be in several transformation slots and they describe themselves as a nomadic project, with the goal of securing new open space for community garden use. The community gardens in the allotments have historical meaning in Berlin. These gardens exist in Berlin since the 19th century, where people were able to grow their own food, but this changed during the Second World War. During this time the small gardens were used as emergency housing to take care of the most vulnerable. Now, these slots offer recreational opportunities for people. Example: The “Kleingartenkolonie am Stadtpark I” in Charlottenburg represents a gathering point for people from the neighborhood to build a stronger community value (Karge, 2021).

Areas for children, This category includes children's farms, playgrounds with community gardens as well as gardening schools. Growing up in a city like Berlin can have the disadvantage of not being in contact with nature. This can lead to children's alienation from nature. For this reason, these gardens focus on teaching children about plants, soils and animals. It is a space where it is easier to understand the responsibility towards the care of nature and the importance of biodiversity within the city. Example: In 1981, next to the Berlin wall in the district of Kreuzberg a garden was founded the „Mauerplatz Kinderbauernhof” where children have a place where they can learn about animals, medicinal plants, vegetables, learn about ecological cycles, and can take responsibility. Community gardens on the grounds of housing complexes are created either on the initiative of the respective housing cooperative, which then invites the residents to participate or by the people living in the building. This space serves to create bonds with neighbors and thus a strong sense of community. There are several examples in Berlin where people got organized and started to use the unused spaces of the buildings in order to have a green space where food could be produced (Karge, 2021).

The gardens in public educational institutions have a long story in Berlin, schools use this tool to approximate the children to the world of food production. Also one of the main ideas is to bring children together so that they learn by themselves about responsibility and awareness of nature. These gardens are also created within universities, where students have the opportunity to make research about biodiversity in Berlin or only to get to know people. Example: The TU Berlin initiated a community garden inside the campus so that students have the chance to put into practice their knowledge and exchange experiences. Company owners, commercial businesses, and entrepreneurs are increasingly emphasizing establishing community recreation areas in and adjacent to private commercial buildings for employees as a balance to the daily office routine. This creates new contacts and perspectives in everyday work. Example: "Idealo Garden" was established in 2016 by members of a company in Berlin with help of the “Prinzessinnengarten”(community garden base in Kreuzberg and Neukölln). Today, 21 raised beds are maintained by employees from the company with the support of the Prinzessinnengärten (Karge, 2021).

Public spaces, in this category the community gardens are in the public park or square areas. In Berlin, there are several projects which are in this kind of area. The “Allmende Kontor” started as an initiative organized in 2010 by civil society to protect the Tempelhofer Feld airport from being part of housing projects. Now it has more than 200 raised beds and people who are involved can exchange knowledge about gardening, beekeeping, compost, etc. The next category is also based in public spaces, streets and parking slots. The street is used as an instrument of community recreation. People from the neighborhood are part of the initiative and take responsibility for diversifying the use of plants in the streets. Example: “Kiezgarten Donaustraße” is located in Neukölln, the project includes a school, a kindergarten and people living in the neighborhood. Different types of workshops related to plant care or food sovereignty are organized (Karge, 2021).

The use of old cemetery as a garden project. The change in burial culture and the associated closure of large areas of cemeteries is creating space for new services on former cemetery sites. The cemetery administrations are faced with the challenge of maintaining the areas despite economic pressure and are thus striving for different forms of cooperation with various actors in urban society. This change of territory allows projects to use large plots of land. For this reason, projects located in cemeteries are usually more ambitious with their cultivation goals. Example: The “Prinzessinengarten” in Neukölln has approximately 2,5 ha of land, where several projects are taking place, like cultivating diverse types of vegetables or plants. The Prinzessinengarten offers several kinds of Workshops where people can usually join without a cost. Some of the main pillars of the project is to interact with civil society and to reinforce a community felling. Art, cuisine, plants, beekeeping, and permaculture are some of the examples that the garden is working on. Community gardens on agricultural fields. are often parts of farms on the outskirts of the city. A plot of land or a strip of arable land can be rented here. Interested parties from all over Berlin rent a plot and often travel a long distance to the garden on the outskirts of the city. Through exchange, workshops, joint garden parties, and with the help of responsible farmers, knowledge is imparted, and community is promoted. Example: the „Meine Ernte” project, in which around 1,500 people provide themselves with fresh organic vegetables and get inspired by professional's farmers with knowledge about the role of responsible farming in our well-being (Karge, 2021).

The history of Berlin has allowed civil society to use urban spaces to its advantage, creating several initiatives promoting the city's sustainable development. Since the beginning of urban gardening and urban agriculture in Berlin, there have been some differences between local authorities and the promoters of the projects, mostly because of the intense bureaucracy work to obtain the permissions to start building the infrastructure of one project (Clausen, 2015). Nevertheless, this process is now changing. Urban gardening and urban agriculture for healthy food production and sustainable agriculture are gaining more attention each year in the municipality of Berlin because the use of municipal land is one of the most relevant levers that municipalities must promote to achieve more ecologically sustainable use of urban space and healthy food consumption within the city (Karge, 2021). The initiatives mentioned above, among others, have made play urban gardening and community garden an essential role in the agenda of the Berlin Senate. The “Senatverwaltung für Umwelt, Verbraucher, Molbilität and Naturschutz” (SvUVMN) has created a department promoting this activity and getting Berlin as a city involved in this movement. This event is of great importance for the community garden movement in Berlin, because not only is there more legal and financial support for new and old projects, but it is now clear that the state of Berlin is also interested in promoting its ideals and achieving above all a healthy environment within the city, where people can interact more closely with nature and at the same time be able to exchange knowledge with the neighborhood (Karge, 2021).

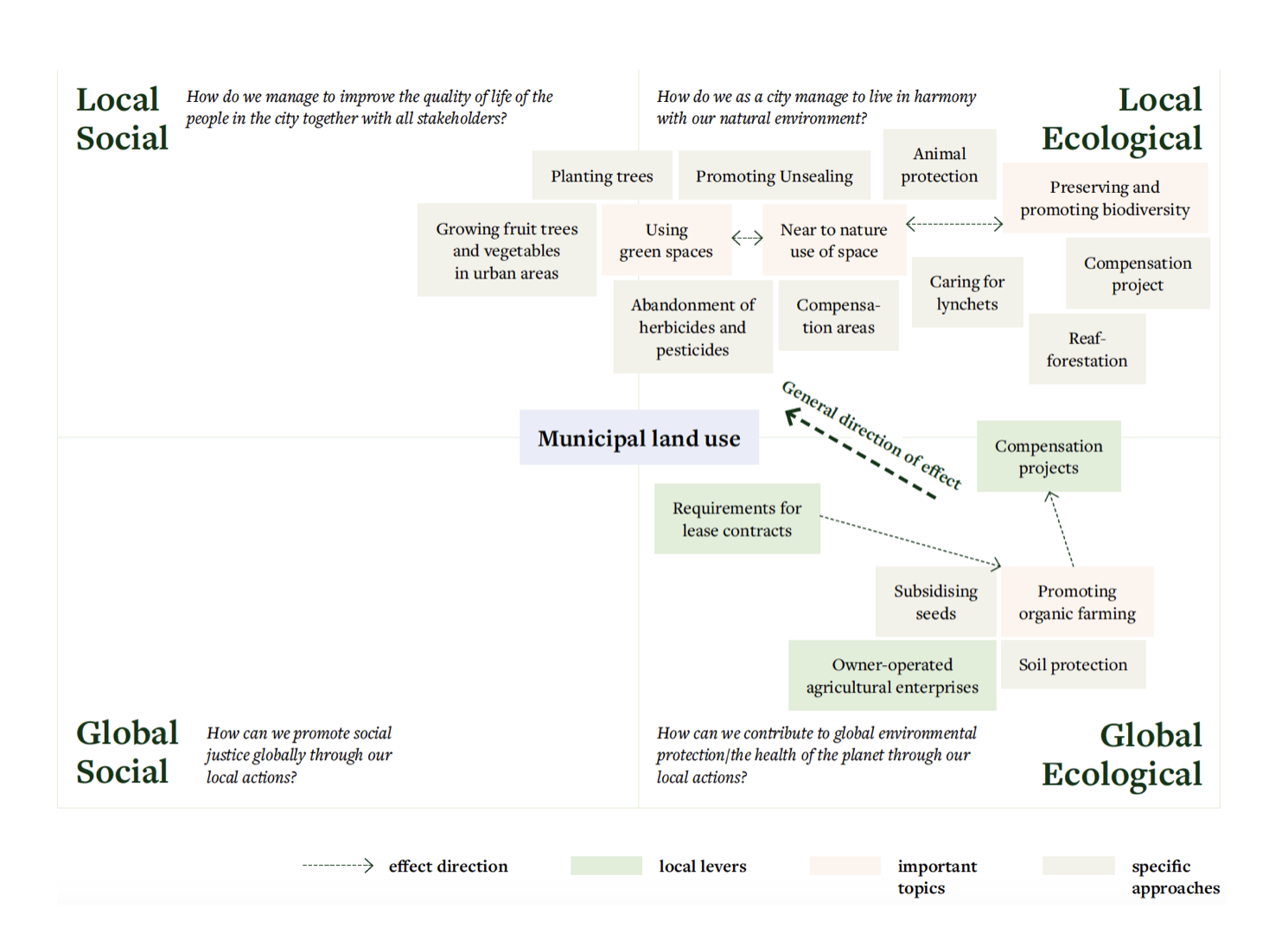

Relating to the principles of the doughnut, urban space use can become an opportunity for preserving and regenerating the environment through sustainable criteria for its allocation and use. In addition, socio-ecological interrelationships goals are considered, enabling community care of gardens, making healthy food freely available, and community values reappear (Strobel & Bothe, 2021). An increase in organic farming not only contributes to environmental protection and a life in harmony with the natural environment but also raises the quality of life of the people in the community (e.g., through access to high-quality products or a reduction in pesticide use). As the figure shows, urban agriculture in a sustainable way can thus contribute to taking greater account of ecological limits in local action. In addition, it can link the environmental impact with positive effects on various social dimensions of the doughnut, e.g making cities and communities liveable, partnership with civil society and increase of mental and physical health (Strobel & Bothe, 2021). The figure illustrates also different measures of urban agriculture in the local social, local ecological, global social, and global ecological indicators of doughnut’s principles. In the category of organic agriculture for example, there are various opportunities to use this tool to contribute to global environmental protection and the conservation of the natural environment. Thus, knowledge is reproduced in a horizontal way, and several attributes of organic agriculture like the use of old seed species are rescued from being forgotten.

III. Urban Agriculture

Fig.2. Strobel Hannah & Bothe Jonas (2021)

Fig.2. Strobel Hannah & Bothe Jonas (2021)The problems regarding agriculture and food are strictly connected to the ecosystems of our planet. If social systems are to satisfy their social needs within the boundaries of the planet, it is required that both agriculture and food systems redesign and reorganize their pattern of production and consumption (Raworth, 2017). Urban agriculture and community gardens can be a tool in this process, as it has great potential to reduce negative impacts on both people and the environment, especially in promoting the protection of the natural environment, environmental conservation and social well-being through new patterns of consumption and production (Strobel & Bothe, 2021). The Senate of Berlin and civil society need to work together to develop new criteria to improve the infrastructure of community gardens so that citizens can leave in a city that cares about biodiversity and the health of ecosystems. This cooperation between civil society and the city of Berlin can lead to reorienting the urban space land of Berlin, giving more opportunities to communities to create more community gardens, to make their city “edible” and support the biodiversity living in the city. This kind of project can generate new economic systems where consumers and local producers can interact with each other, have a more transparent and healthy food chain, and develop new marketing and food distribution systems (Strobel & Bothe, 2021). Through this journey, it became more than clear how much the 200 or so community gardens in Berlin differ from one another in terms of their origins, organization, programs, and possible development, despite having a common basic understanding. In addition, the spectrum of gardens is continuously expanding: new garden forms on commercial roofs and cemeteries or in allotment gardens are being added to the familiar garden forms. Some of these community gardens are independent, others are characterized by multiple uses in the area, which gives rise to new questions and contexts of common use. There are several challenges that community gardens must deal with, but one of the main challenges is that community gardens do not fit into existing open space categories. As Berlin becomes more densely built, the number of available spaces decreases, therefore community gardens projects are often unsecured and under threat (Karge, 2021). In addition to innovative ways to secure the existing gardens, the task of activating new space potential should increasingly take a central role in Berlin's urban planning future. The diversity of Berlin's community gardens is great and should remain so, but this also requires dealing with a wide range of different framework conditions in the future.

References

- Clausen, Marco (2015) Urban Agriculture between Pioneer Use and Urban Land Grabbing: The Case of “Prinzessinnengarten” Berlin, Cities and the Environment (CATE): Vol. 8: Iss. 2, Article 15.

- Clausen, M. (2016), MAZI-Projekt: locale digitale Netzwerke, Nachbarschaftsakademie, viewed 31 July 2019. Available at: https://prinzessinnengarten.net/10090/

- Clausen, M. (2013), “Community based urban agriculture and resilient food systems from a bottom-up point of view”, in 5th AESOP Sustainable Food Planning Conference “Innovations in Urban Food Systems. Available at: https://prinzessinnengarten.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Prinzessinnengarten_5AesopFoodPlanning.pdf

- Fukuoka, Masanabou (1978). One-straw revolution. Rodale Press.

- Strobel Hannah & Bothe Jonas (2021) A doughnut a day keeps the doctor away, NELA e.V., 2021

- Karge, Toni (2021). The Berlin Community Garden Program / das berliner gemeinschaftsgarten- programm. Urban Open Space+, 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783868599848-015

- Raworth, K. (2017), Doughnut Economics: seven ways to think like a 21st century economist. London: Penguin Random House.

- Urban gardening manifest. Urban Gardening Manifest. (n.d.). Retrieved August 16, 2022, from https://urbangardeningmanifest.de/

- Wendler, J. (2014), “Experimental urbanism: grassroots alternatives as spaces of learning and innovation in the city”, doctoral dissertation, University of Manchester. Available at: https://prinzessinnengarten.net/wpcontent/uploads/2015/02/alternative-experiments_jana-wendler_LR.pdf