"Ecobarrios" in Bogotá - Towards a 'generous cities' strategy based on Abya Yala alternatives to development

Updated at 24.08.2022

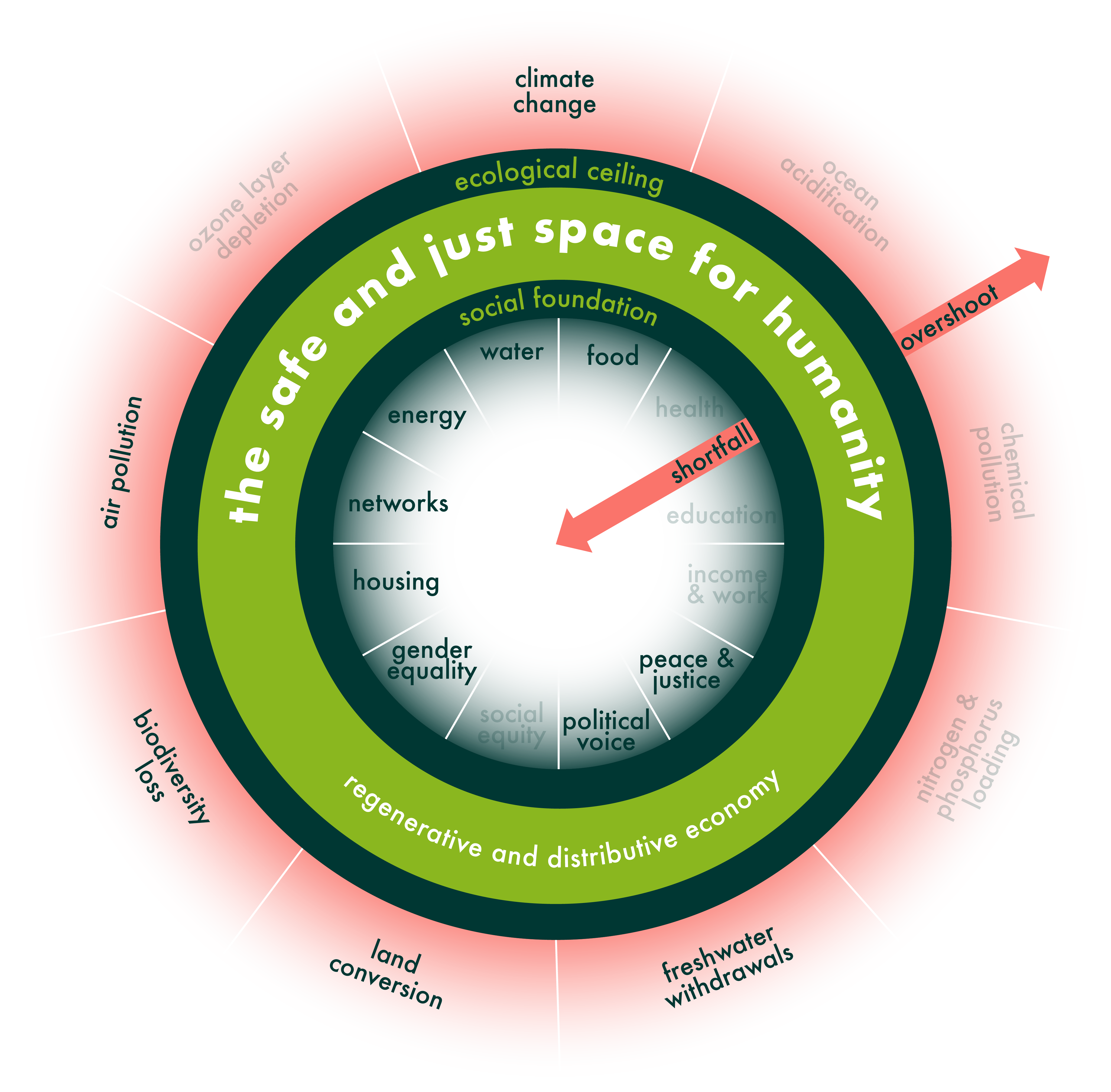

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subject

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subjectI. Introduction

As a global key factor in social and environmental (UNEP, 2020) degradation, urban areas draw the public attention in seeking solutions to overcome their unsustainable functioning. In this regard, "Ecobarrios" or “eco-neighborhoods" is a living proposal created by different communities worldwide for more than thirty years.

Herein, the experience of "Ecobarrios" in "the Bogotá Eastern Hills"-Colombia is analyzed, starting with their historical evolution and conception, followed by the fundamental features in the light of “the doughnut economy model” (Raworth, 2017). The latter means that the "Ecobarrios" contribute to an “embedded economy” (Raworth, 2017) and its participation in both the social foundation and the planetary boundaries model.

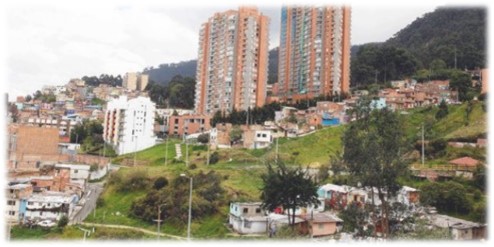

Fig.1. Tall buildings: Gentrification Bosque Calderon Neighborhood (El Tiempo, 2015)

Fig.1. Tall buildings: Gentrification Bosque Calderon Neighborhood (El Tiempo, 2015)II. What is going on?

Looking at the trajectory: Bogotá and its Eastern Hills

According to the National Administrative Statistics Department (DANE, 2021), the Colombian transition from a rural to an urban country was determined by migratory movements as a result of the armed conflict since the 20th century, where victims of forced displacement and internal migrants came from the countryside to the peri-urban areas. DANE asserts, that the "population is forced to request shelter from relatives or to build houses with waste materials in areas that have a low access to public services and, in many cases, are at risk of disaster" (DANE, 2021), by occupying land through invasions or informal market housing.

Thus, cities extended their areas, taking in surrounding municipalities and/or being densified again conflictingly. Therein, "the role of landowners, developers, financial agents (…) municipal entities in charge of planning" (DANE, 2021), and illegal stakeholders and citizens were crucial in the urban growth and stresses. The Bogotá city urban development evolved according to the same trend.

Being one of the most relevant cases of urban conflicts in the capital city, the "Bogotá Eastern Hills'' is home to a total of “91.000 inhabitants, and 19.000 of them on the south side” (El Tiempo, 2016), comprising of “14.000 acres approx. (140 km2)” (Sánchez Beltrán, 2019). This area was inhabited by "Muisca" indigenous communities in Pre-Columbian times and, afterwards, one part was used as the capital of the Spanish colony, reporting since 1520 the "first fragmentation and disturbance of the ecosystem" (Fundación Cerros de Bogotá, 2020) due to the colonial dominance and the spread of overexploitation of “stone, firewood, and wood” (Fundación Cerros de Bogotá, 2020). By the 18th Century, numerous estates appeared, and these properties became brickworks, mining of stone and sand in the 19th and 20th Centuries, even though in 1930 some small reforestation projects began with foreign trees.

The dynamics in the Bogotá Eastern hills became more conflictive after the mid-20th century. According to Sánchez Beltrán (2019), before these hills were declared a “forest reserve” in 1977 by the National State, “There were innumerable mines of sandstone and coal, which atrophied part of the native flora and fauna of the high Andean Forest that covered them. Those who lived in the hills were mostly mine workers or peasants. (…) who live there between 50 to 100 years ago” (Sánchez Beltrán, 2019).

Although the Colombian State intended to protect the connection between moorlands “as water regulator for the supply of the service to the inhabitants of the capital prohibiting any kind of construction” (Sánchez Beltrán, 2019), this measure was harmful to the vulnerable population who already lived there and the new ones “who bought a low price small land because some cheating landowners plotted their huge properties to not lose their investment between the 80s and 90s" (Sánchez Beltrán, 2019).

Since then, the vulnerable population is striving to legalize their neighborhoods and not be expelled by resettlement. However, the conflict escalated in 1997, when the other, older landowners used a legal limbo from the new national urban planning legislation and obtained building permits for real estate projects. Sánchez Beltrán (2019) says that these new constructions “devastated irreversibly much of the forest reserve” and, at the same time, with the rising national power of paramilitaries since 2000, “displaced families reoccupied ruined houses in the Bogotá Eastern hills by invasion, creating new conflict between neighbors” (Sánchez Beltrán, 2019).

Moreover, Sánchez Beltrán (2019) describes that, later, in 2005, Sonia Ramírez sued the Bogota government's decision, achieving an end the construction by the big real states until 2013. Then, the Court's ruling commanded a " Belt of Adequacy" made up of a public priority occupation and an urban edge area, respecting the already acquired legal building permits.

Some activists consider that ruling is in favor of gentrification, since real estate companies and the Bogotá government are planning public mega projects for ecotourism like “Sendero de las Mariposas" and most of the communities' houses were made without building permits.

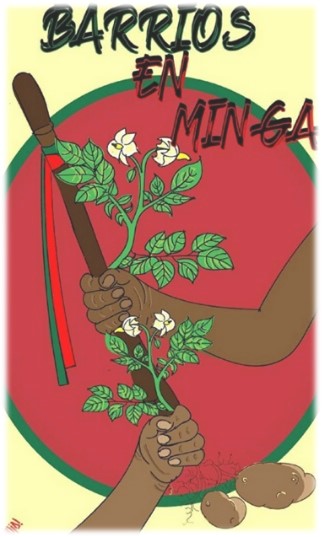

Fig.2. Minga: Indigenous word used now in urban activities. (2020)

Fig.2. Minga: Indigenous word used now in urban activities. (2020)Looking at the trajectory: Bogotá Ecobarrios experience and concept

According to Álvarez Cubillos (2010), the “Ecobarrios project” popped up in 2001 as a part of a Bogotá government policy, based on informal grass-roots organization, and the formal civic organizations named by law "Juntas de Acción Comunal-JAC" to support the communities affected by the hegemonic urban development.

This project “tried to change communities’ behaviors and motivate both participation and capacities for alternative urban development. It implemented communitarian diagnostics in 143 neighborhoods, identifying small projects that inhabitants wanted to work on to improve their living conditions, like pedestrian walkways, tree planting in common areas with productive and native trees, as well as meeting spaces such as schools, community halls, and libraries, where to take place artistic, cultural, technological activities and there were resources to be used by the communities. (…) As a result, the democracy, and the identity especially of children and teenagers were much more eco-human sustainable.” (Álvarez Cubillos, 2010)

This is the reason why, relying on the Bogotá Eastern hills experience, Álvarez Cubillos defines Ecobarrios as “a group or community of people with a common vision focused on the long term, that is organized to improve their quality of life and achieve human well-being, in harmony with the environment of urban space. These people groups can exist as small neighborhoods in the middle of a huge metropolis or as whole villages in rural areas.” (Álvarez Cubillos, 2010) This notion moves away from the global north “Ecobarrios” concept based “on the “eco-urbanism” field, where technology and ecology are connected to achieve an urban sustainable development ” (Álvarez Cubillos, 2010).

Despite this difference, Álvarez Cubillos considers Ecobarrios as “a global tendency, where urban spaces are designed to minimize the impact on nature.” (Álvarez Cubillos, 2010), and he recognizes “eco-village” global experiences in rural areas as an influence in this proposal.

In addition, Álvarez Cubillos proposes that “the functioning of eco-neighborhoods is underpinned on the generation of social relations that at the same time is founded on a.) participation in the common construction, recognizing members' differences, b.) the saving and efficiency of basic resources, c.) the sustainable use of renewable energies, d.) the handling and management of pollution, e.) the integration of agriculture with nature, f.) the promotion of sustainable mobility methods, g.) the creation of "agropolis", understood as cities in creative lookup of harmonious relations between citizens and nature.” (Álvarez Cubillos, 2010)

Fig.3. Alto Fucha Urban Garden supports by Huertopía. (Huertopía, 2021).

Fig.3. Alto Fucha Urban Garden supports by Huertopía. (Huertopía, 2021).Looking at “Ecobarrios” through the lens of the “Doughnut Economy”

On the one hand, in ensuring “the right to the city” for lower classes, Ecobarrios is a strategy that can reinforce “the commons”, as Kate Raworth proposes in her “doughnut economy model” (2017). In addition, acting as a “network design”, Ecobarrios redistributes some flows of power, wealth, and rent, and thus it holds an outstanding potential that could be implemented in future local production initiatives like “community maker-spaces”.

Looking in detail at the flow distribution design (Raworth, 2017) at the Ecobarrios local level, it is related to actions that improve land property, labor for urban renewal, and political-community participation. Even so, its stability depends significantly on both support and regulation from the state, as well as the redirection of financial flows and other wealth factors, coming from stakeholders beyond civil society such as banks and entrepreneurs. These new organizations should have a “living purpose” (Raworth, 2017) concept to operate according to the doughnut model.

Turning now to the Ecobarrios potential factors, the most relevant is the formation of “learning communities and societies for coexistence, participation, conflict resolution, and sustainable relationship with the local environment and its connection with other levels” (Álvarez Cubillos, 2010). Then, the socialization of the members and their backgrounds are comprehended as an educational and pedagogical process to empower them as individuals, communities, and society.

Furthermore, there are essential cultural features in order to move past the "rational economic man" notion as Raworth (2017) proposes. In this way, Anamaría Aristizabal and Carlos Rojas (Rojas & Ome, 2009) consider that, in looking for reconciliation, Ecobarrios dialogue with the Abya Yala (continental American) indigenous cosmovisions. They claim that “indigenous grandparents give us two pieces of knowledge about communitarian life: the silent and emotional knowledge, that western culture forgot. The first means the ability to observe, understand our emotions, and the second is the no word knowledge with meaningful information, and energy to bind and strengthen a community, like art, ritual, dance, prayer, meditation, collective food preparation, collective sowing of seeds, care of plants and animals, music, celebration, and aesthetics.” (Rojas & Ome, 2009)

Likewise, Rojas & Ome (2009) identify the "social indigenous technology" as a method to steward Ecobarrios by: a.) clearing the word, eliminating unnecessary words like generalizations and control over others, b.) cleansing the mind, not judging others, putting yourself in each other’s shoes, c.) cleansing the heart, feeling unity with the others as an equal.

On the other hand, the regenerative process design (Raworth, 2017) at the Ecobarrios local level is related:

- On one hand, Ecobarrios allow some initiatives to stay within the social foundation. As Raworth (2017) says, that is understood as just an inner boundary that meets human rights necessities. Ecobarrios fulfill some dimensions, such as i.) Water, ii.) Food, iii.) Peace and justice, iv.) Political voice, v.) Gender equality, vi.) Housing, vii.) Networks, and viii.) Energy.

- On the other hand, in understanding the planetary boundaries as an ecological ceiling (Raworth, 2017), Ecobarrios' actions contribute to reducing the pressure on some earth systems, such as i.) Climate change, ii.) Land conversion, iii.) Freshwater withdrawals, iv.) Air pollution, and v.) Biodiversity loss.

Avoiding the deprivation: Social foundation in Eastern Hills Ecobarrios.

There are many examples of Ecobarrios in the Bogotá Eastern hills that relate to initiatives addressing the social foundation. Let's explore each dimension:

- Water: According to Álvarez Cubillos (2010), communities care about the water bodies. They have projects for preserving springs, like cleaning and limiting use. One example is the cleaning activities in the “La Vieja” stream, at the Salitre” central basin. As well, communities have projects to use home water recycling systems, dry toilets, rainwater harvesting, and reforestation.

- Food: Other Ecobarrios are focused on urban gardens. As Sánchez Beltrán (2019) claims, e.g., in the "Laureles" illegal neighborhood at "La Fucha" high south basin, the communities are growing vegetables, and herbs in public, community and private spaces alongside handling solid waste in composting. Indeed, one beautiful process is led by a communitarian group called "Huertopía", which supports the communities with technical advice, seeds, and seedlings.

- Peace and Justice: The communitarian actions recover the public space from conflict factors. For example, “Huertopía” (Sánchez Beltrán, 2019) recuperate abandoned public space with gardens and workshops, avoiding that places are used for drug micro trafficking and, thus, they improve the security perception and families can enjoy these spaces.

- Political voice: Ecobarrios have a diversity of political organizations. The formal communal organizations (JAC) are highlighted because they are responsible for a number of neighborhood topics based on the neighbors' participation. A lot of JACs are associated with an enter-risk neighborhood political body to fight for the right to remain in their territories called the "Commission in Defense of the Alto Fucha Territory", which is negotiating with government urban planning in the area, like the " Belt of Adequacy”.

- Gender equality and Networks: Ecobarrios encourage the care work discussion and the recognition of women's roles. In this case, women's participation and leadership are becoming much more significant in ruling the territory. In this path, actions for network creation are crucial, for example, the "Tejedoras de sueños" project in the Aguas Claras neighborhood calls “all women to think about their territory, in their future as entrepreneurs and creatives, through the "Yarn bombing" technic” (Pretel, 2021) at the “Mandalas” forest.

- Housing and Energy: Ecobarrios' housing projects are funded by the Bogotá government and some European embassies, as well as international cooperation, which is relevant in the south side of Bogotá Eastern hills. One example is the "eco-houses" project in the Manantial, Triángulo Bajo, and Triángulo Alto neighborhoods, where "wood, guadua, and other sustainable materials are used, as well as sunlight to illuminate homes, and rainwater for domestic chores." (Nodos de Biodiversidad, 2019) Of course, this concept is used in the public space infrastructure too.

Fig.4. Mandala Forest (Sánchez, 2019)

Fig.4. Mandala Forest (Sánchez, 2019) Fig.5. Eco-house in Manantial neighborhood (Diana Rey-Semana,2020)

Fig.5. Eco-house in Manantial neighborhood (Diana Rey-Semana,2020)Staying in a safe operating space: Planetary Boundaries in Eastern Hills Ecobarrios

The planetary boundaries approach “aimed to define the environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate. (…) based on critical processes that regulate Earth System functioning.” (Steffen, et al, 2015), meaning the intrinsic biophysical processes.

For this, the PB framework identifies a safe operating space, which implies that “levels of anthropogenic perturbations are below, and the risk of ES destabilization is likely to remain low.” (Steffen, et al, 2015) Likewise, it proposes a zone of uncertainty for each (…) area of increasing risk to destabilize ES” (Steffen, et al, 2015) relating to anthropogenic excesses. They clarify that the “proposed PB is not placed at the position of the biophysical threshold but rather upstream of it—i.e., well before reaching the threshold. (…) that affect the capacity of the Earth system to persist in a Holocene-like state” (Steffen, et al, 2015)

Steffen. et al (2015) recognize that, even though PB considers “a global/continental/ocean basin level” (Steffen, et al, 2015), the dynamic in every dimension is made up of many heterogeneous spatially processes, which are necessary “to define sub-global boundaries that are compatible with the global-level boundary definition.” (Steffen, et al, 2015) to implement them. They make it clear that the unities are different in every boundary, despite “the biosphere integrity occurs at the level of land-based biomes” (Steffen, et al, 2015).

In this regard, the identification of Bogotá’s contributions towards the global regional boundary is uncertain. However, Ecobarrios comprehends that “urban ecosystems act as a metabolism, where energy, organic and waste, water, atmospheric and hydrologic processes” (Secretaría Distrital de Planeación, 2014) must adapt themselves to the ecological ceiling. As follows, there are some examples of Ecobarrios’ contribution to staying in the safe operating space:

- Climate Change: It is estimated that there will be an “increase of 2- and 2,3-degrees temperature and 10%-20% precipitation in Bogotá. These changes impact too much on sensitive moorland ecosystems, where we took the water, also it's probably lost 50% of moorlands and 70% of high mountain forests” (El Tiempo, 2016). Some researchers clarify that this trend depends on a scenario “with rapid changes in economics structures leading by services and information, alongside fewer intensive materials using and clean technology’s introduction” (Rodríguez-Pérez & Beltrán-Vargas, 2014) Otherwise, in scenarios with current fossil fuel use or half-measures, the increase is over 4 degrees (Rodríguez-Pérez & Beltrán-Vargas, 2014). Facing this forecast, Ecobarrios can increase their reforestation and afforestation projects and deepen their role as forest guardians, since the forest reserve acts as a cooler and carbon sink, helping to stay between “14-16 degrees in 2040-2095” (Rodríguez-Pérez & Beltrán-Vargas, 2014), instead of “16-18 degrees” (Rodríguez-Pérez & Beltrán-Vargas, 2014) described in the worse scenario.

- Land conversion: According to Sánchez Beltrán (2019), erosion and landslide risk are principal problems in the Eastern Hills, alongside small-scale deforestation participation and illegal mining. As such, the improvement and conservation of vegetation cover and the forest is one of Ecobarrios’ goals. As Álvarez Cubillos (2010) says, Ecobarrios encourage projects for conservation and sustainable land use developed by the community and state, as well as reforestation projects with native species next to water bodies or as part of biomechanical networks, and the use of the sewerage systems.

- Freshwater withdrawals: According to the Secretaría Distrital de Planeación (2014) Bogotá is disrupting “the water hydrological cycle due to a.) the urban waterproofing and reduction/ change of vegetation cover, b.) discharging of solid and liquid waste into the water bodies, c.) not using of green technologies to specialize the drinking water and building demand” (Secretaría Distrital de Planeación, 2014). To overcome these issues, Ecobarrios have made progress on its public infrastructure, and its housing policy based on sustainable construction, plus water conservation measures on the upper side of the streams. However, it could be insufficient if the city water policy continues to deplete water outside the forest reserve.

- Air pollution: “In Bogotá, it is a fact that air pollution is caused mainly by the use of fossil fuels, emitting pollutants such as the particulate matter of (PM), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2) ozone (O3 ), nitrogen dioxide (NO2 ) and sulfur dioxide (SO 2 ), all of which are associated with the emissions from vehicle fleet and industry, deteriorating air quality, it has caused an increase in the negative effects on human health and the environment.” (Secretaría Distrital de Planeación, 2014) As Sánchez Beltrán (2019) claims, in the Eastern Hills, that the air quality is less polluted than in other Bogotá city areas, even though it exceeds the legal goal. As such,, Ecobarrios not only protect the forest but also have the potential to adopt public transportation strategies and service infrastructure that can be found by citizens by walking.

- Biodiversity loss: Bogotá “must improve ecological connectivity. Currently, the city has 1.000 flora species, and 494 species are in the Eastern hills, as well as in fauna more than 1.000 species between invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals” (Secretaría Distrital de Planeación, 2014). In this way, Sánchez Beltrán (2019) asserts that, in the Alto Fucha basin, inhabitants observe owls, water blackbirds, hummingbirds, Andean turkeys, clarineros, toches, hawks, and less frequent animals such as crayfish, savannah snakes, wild rabbits and cusumbos, and at least eleven butterfly species. Relating to vegetation, “the dominant are Eucalyptus, pine, and acacias, however, gradually the area has been restored without human intervention especially on the riverbank finding native species such as chusque, lupino, trumpet, fuchsia, chicalá, tihiki, bear hand, among others.” (Sánchez Beltrán, 2019) As such, Ecobarrios can protect the mobility and habitat of these living beings due to their coexistence in the forest and environmental education projects.

Fig.7. Eco-houses in Manantial neighborhood. (Carlos Lince)

Fig.7. Eco-houses in Manantial neighborhood. (Carlos Lince) Fig.8. Ocellated owl at Alto Fucha (Sánchez,2019)

Fig.8. Ocellated owl at Alto Fucha (Sánchez,2019)The scope of the social networks: Current state of Ecobarrios stakeholders

The stakeholders involved in the Bogotá Eastern hill Ecobarrios have been diverse for more than forty years. The core of this strategy are the grass root associations, followed by other civil society organizations like NGOs, churches, research institutes, and universities.

In this way, civil society organizations like: “Aldeafeliz, Red Colombiana de ecoaldeas, Fundación para la Reconciliación” (Rojas & Ome, 2009), CINEP institute, and others have redirected their support towards Ecobarrios communities to improve their capacities through educational and participatory projects and supporting their struggles. In the past decade, international cooperation organizations and European embassies have worked together with the Ecobarrios communities on projects relating to sustainable infrastructure and democracy.

Over time, the Ecobarrios concept spread over Colombia and developed in new neighborhoods in Medellín and Cali, like Ecobarrio Los Sauces and Suerte 90, respectively. These efforts have led to local governments adopting this concept as a habitat policy.

Coming back to Bogotá, the current government considers Ecobarrios as a mitigation measure to improve urban forests and rural areas on the city’s edge, according to SDG 11. Thus, these new projects are looking forward to enhancing “a.) efficient water, heating, lighting, acoustic, and ventilation use, b.) energy saving and efficiency, c.) green infrastructure, and d.) Efficient handling of waste and materials” (Ramírez, 2022). For instance, the government has invested approximately 84.000 Euros in the Ecobarrio La Perseverancia and recognized it formally. (Ramírez, 2022)

According to Alberto Ruz Buenfil (Casa Latina, 2022), during the last two decades, the “Arcoiris por la Paz” caravan was disseminating the “eco-village” experiences over more than seventeen countries in South America. In this exchange, the Bogotá Ecobarrios experience inspired alternative ways of inhabiting urban spaces throughout the whole region. This has led to the Ecobarrios concept existing in countries like Mexico, Chile y Argentina. Likewise, Laura Esquivel (Casa Latina, 2022) asserts that Ecobarrios processes already exist in Brazil and other countries.

III. Conclusion

Ecobarrios is a glocal strategy toward sustainability in Cities, being able not only to stop socio-ecological damage but also to regenerate the socio-ecological processes that allow life. Its evolution highlights its potential as a flow distribution design as well as a regenerative process design that is inset very well in the doughnut economy model, due to its daily actions contributing to the social foundation and planetary boundaries.

The uniqueness of this concept is its strong communitarian approach that dialogues with other knowledge forms, such as the indigenous cosmovision, to resolve urban conflicts.

To flourish and remain stable, Ecobarrios requires other stakeholders in an embedded economy, like the commons, as well as households, but mostly the states and entrepreneurs. Ecobarrios currently have a significant support network that can be expanded to “Cyclical (so-called circular) economy” (Raworth, 2017). Moreover, the scope of Ecobarrios' actions depends on changes in other urban factors like transportation, industry, energy, housing, and agriculture supplies policy.

References

- Álvarez Cubillos, H. H. (2010). Pensando en Ecobarrios: Una propuesta a las políticas de reasentamiento y políticas de Hábitat. Bogotá: CINEP. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/escobarriossc/docs/ecobarrios

- Casa Latina. (2022, 03 4). Lanzamiento del libro Ecobarrios en America Latina. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/RedCASAlatina/videos/3166821286883337

- DANE. (2021). Informes de Estadística Sociodemográfica Aplicada # 7: Patrones y tendencias de la transición urbana en Colombia. Bogotá: DANE. Retrieved from Informes de Estadística Sociodemográfica Aplicada # 7: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/poblacion/informes-estadisticas-sociodemograficas/2021-10-28-patrones-tendencias-de-transicion-urbana-en-colombia.pdf

- El Tiempo. (2016, 12 28). Especial: Protección para los cerros orientales en Bogotá. El Tiempo. Retrieved from https://www.eltiempo.com/multimedia/especiales/proteccion-para-los-cerros-orientales-en-bogota/16746584/1/index.html

- Fundación Cerros de Bogotá. (2020, 10 13). Historia de los Cerros Orientales. Retrieved from Fundación Cerros de Bogotá: https://cerrosdebogota.org/index.php/historia-de-los-cerros/

- Nodos de Biodiversidad. (2019, 03 02). Ecobarrios: una alternativa sustentable de ciudad que emerge en los Cerros Orientales de Bogotá. Retrieved from Conexión Bio-2021. Nodos de Biodiversidad: https://conexionbio.jbb.gov.co/ecobarrios-una-alternativa-sustentable-de-ciudad-que-emerge-en-los-cerros-orientales-de-bogota/

- Pretel, A. R. (2021, 08 15). Las mujeres del Alto Fucha tejiendo bosque. Retrieved from Secretaría de cultura, recreación y deporte: https://www.culturarecreacionydeporte.gov.co/en/las-mujeres-del-alto-fucha-tejiendo-bosque-0

- Ramírez, L. (2022, 01 17). Alcaldía de Bogotá. Retrieved from ¿Qué son los ecobarrios? Apuesta del Distrito para reverdecer a Bogotá: https://bogota.gov.co/mi-ciudad/habitat/que-son-los-ecobarrios-de-bogota-y-como-ayudan-al-medioambiente

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics : Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-century Economist. London: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Rodríguez-Pérez, J., & Beltrán-Vargas, J. (2014, 03 29). Analysis of climate change scenarios A1B, A2 and B1 for protective forest reserve Bosque oriental de Bogotá, years 2040, 2070 & 2095 with MarksimGCM. Revista Científica, pp. 166–183. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.14483/23448350.5595

- Rojas, C., & Ome, T. (2009). Ecobarrios en Bogotá, ¿cómo crear una comunidad ecológica? Papeles de relaciones ecosociales y cambio global, 167-173. Retrieved from https://www.fuhem.es/papeles_articulo/ecobarrios-en-bogota-como-crear-una-comunidad-ecologica/

- Sánchez Beltrán, J. K. (2019). Aportes desde la agroecología para habitar el alto Fucha desde la noción de ecoterritorio : una apuesta de huertopía para la permanencia en los Cerros Orientales de Bogotá. (U. P. Nacional, Ed.) Retrieved from Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Repository: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12209/12010

- Secretaría Distrital de Planeación. (2014). POLÍTICA PÚBLICA DE ECOURBANISMO Y CONSTRUCCIÓN SOSTENIBLE. Bogotá: Secretaría Distrital de Planeación.

- Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E., . . . Sörlin, S. (2015, 02 13). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science, 347, 736-747. Retrieved from https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/science.1259855

- UNEP. (2020, 10 26). UN Environmental Program/Goal 11: Sustainable cities and communities. Retrieved from https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/sustainable-development-goals/why-do-sustainable-development-goals-matter/goal-11