Green Justice: Initial Reflections on the National Green Tribunal of India

Updated at 31.08.2022

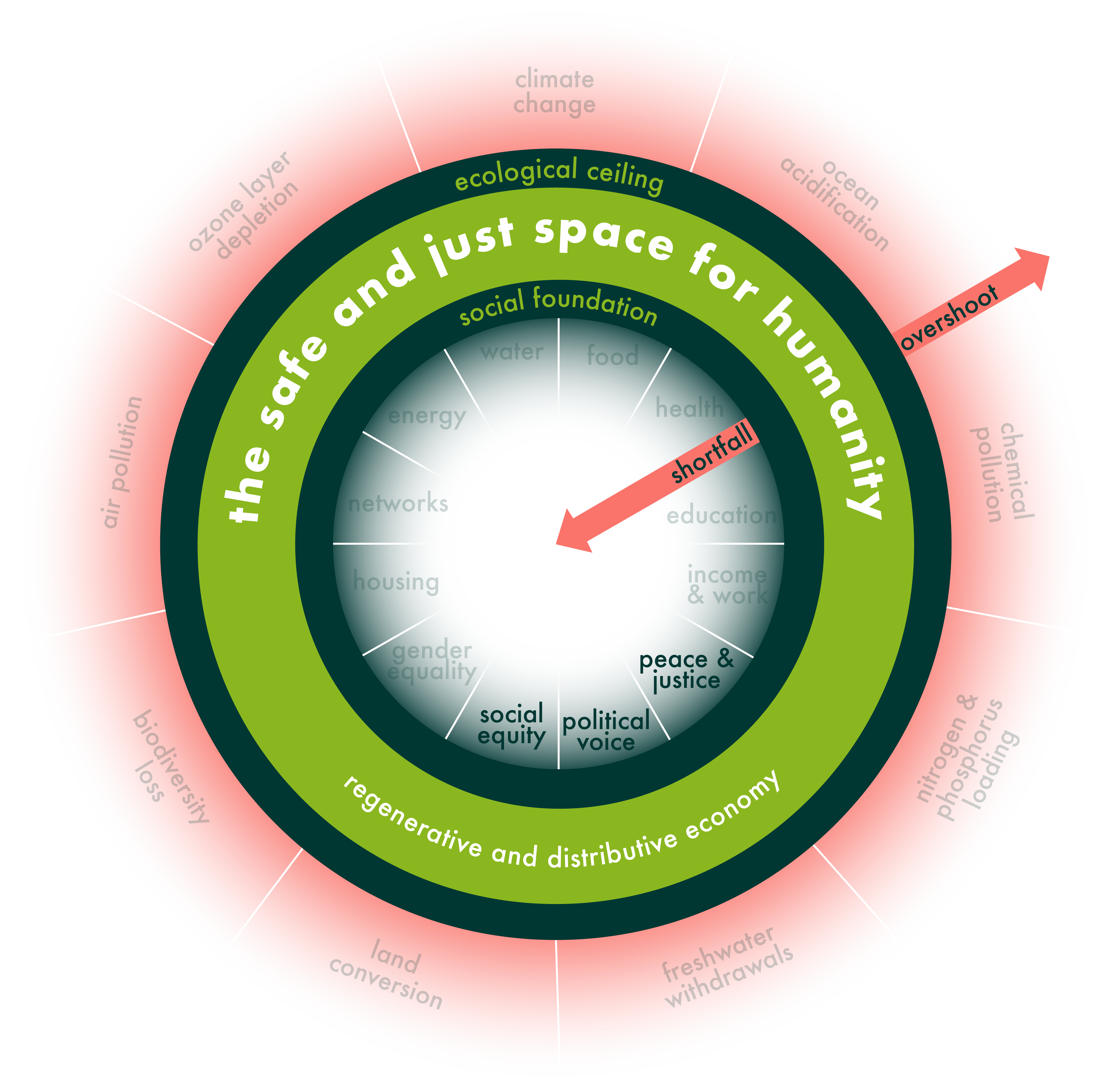

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subject

Doughnut showing dimesions affected by this subjectI. Introduction

The Anthropocene is a scientific term used in geological timescales to signify the impact of single dominant species (humans) on the ecosystem that has altered the fate of all other species and the planet at large (Jannat, 2018; Rodríguez-Garavito, 2021b). As explained in the introduction, the doughnut model consists of two concentric rings. The inner one represents the social foundation associated with human well-being, and the outer ring represents the ecological boundaries popularly known as planetary boundaries. Human rights, the fundamental right to a clean environment, and access to justice in case of any violation are the crux of the problem ensuring proper enforceability of actions and solutions required to strike an appropriate balance between social foundations and the ecological ceiling, i.e., social development while making sure the environment is not damaged.

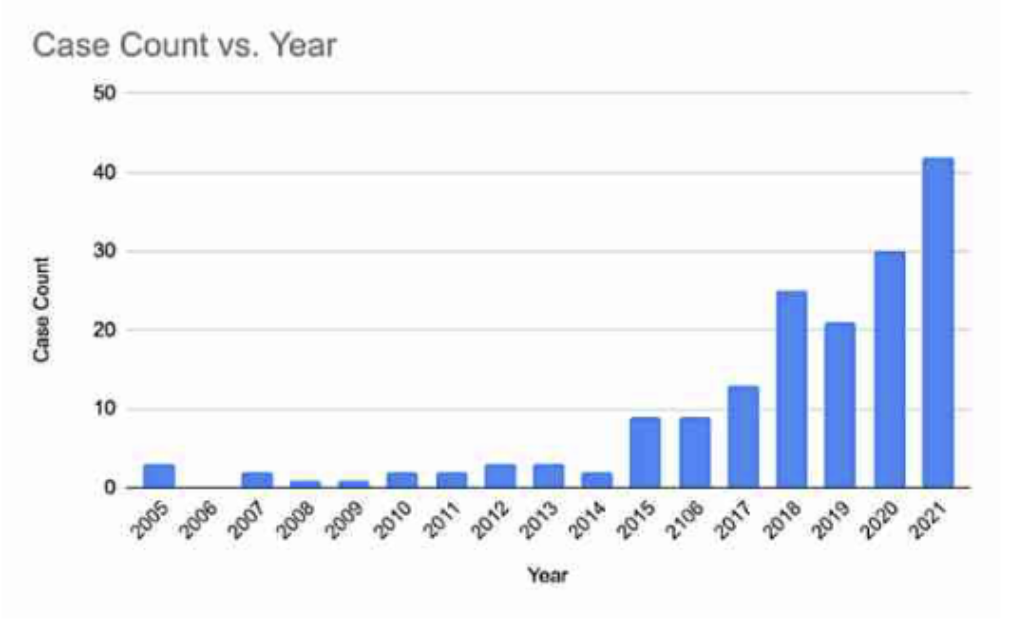

The 2019 Dutch Supreme Court’s ruling in the Urgenda case (Rodríguez Garavito, 2021a) provided the foundation for the German Constitutional court judgment, which in April 2021, led to an increase in Germany's 2030 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction target. In June 2022, in West Virginia vs. USA EPA, the US supreme court clipped the powers of the US EPA in regulating GHG emissions (Mahase, 2022). The common factor of these cases is that they were litigated in general (civil) courts based on the constitution and principles of those countries. These cases follow a typical template of human rights-based climate change (HRCC) and have seen a rise since 2015 (refer to Figure 1). The HRCC cases occur at two levels, i.e., national and international questioning standards and the government's legal obligations in reducing GHG emissions and their policies. (Rodríguez Garavito, 2021a) provides a global database of such cases from 2005 to 2021. As rosy as it looks, in these types of ligations science-based decision-making is most probably not the top priority; for example, the civil law protection of the environment looks into the compensation of damages, obligations and property rights rather than looking into crux of the issue (Krstinic et al., 2017). Moreover, the technical and scientific uncertainty surrounding the issues relating to climate change would complicate the proceedings further (Jasanoff & Nelkin, 1981).

Fig.1. HRCC cases filed per year (Rodríguez Garavito, 2021a)

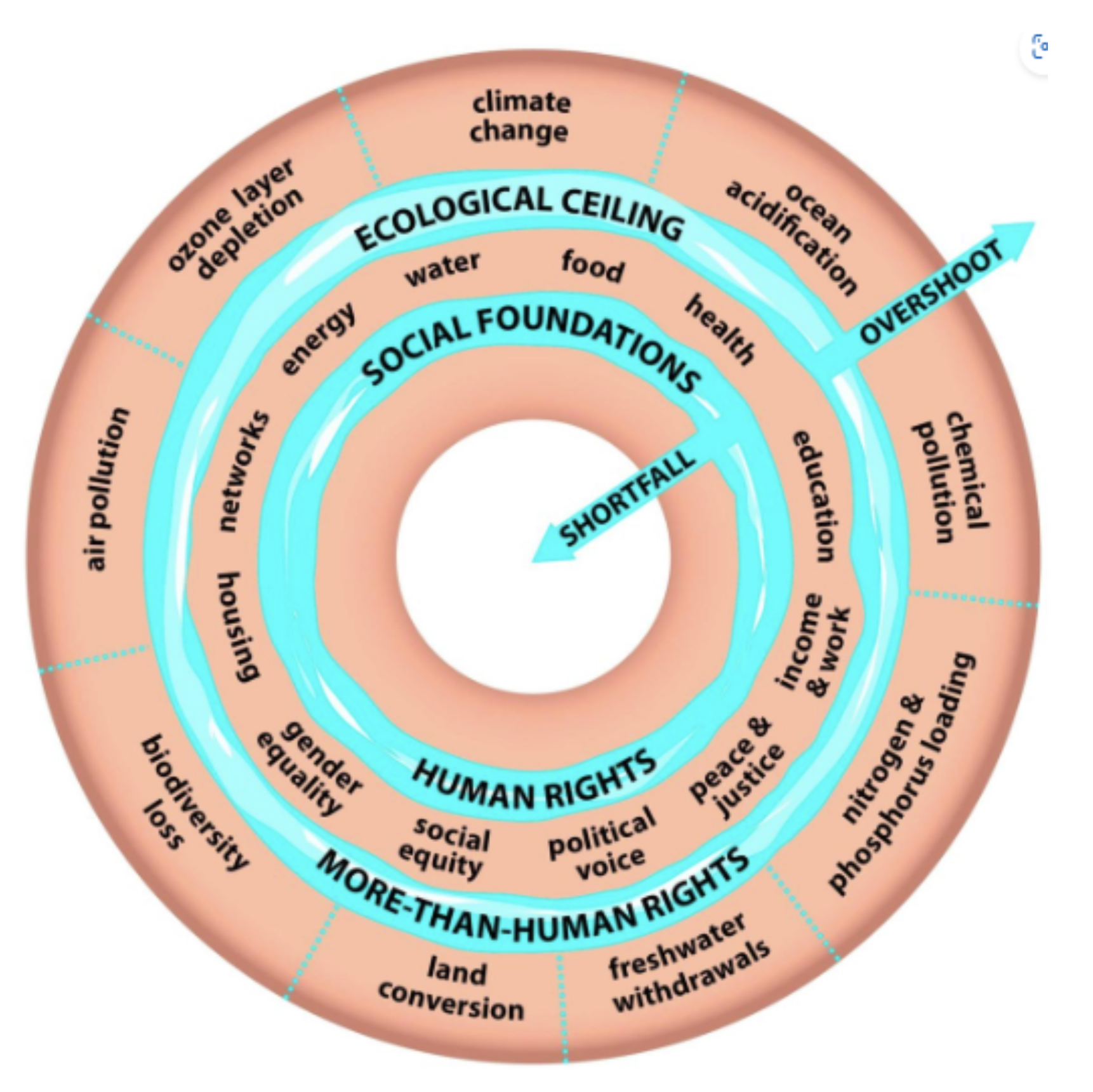

Fig.1. HRCC cases filed per year (Rodríguez Garavito, 2021a)In addition to human rights, economic and social rights are also critical components when it comes to HRCC and climatizing human rights in general. Now, when we apply Kate Raworth's doughnut model to address the legal and rights-based litigation (doughnut law as shown in Figure 2), then it would have to address the regulation & protection of ecosystems, managing requirements, balancing companies and people, as both would not prefer a regulatory regime, and finally, the law should be based on science-based approach (Jannat, 2018).

Fig.2. Human rights and Doughnut model (Rodríguez-Garavito, 2021b)

Fig.2. Human rights and Doughnut model (Rodríguez-Garavito, 2021b) II. National Green Tribunal (NGT) India

Access to environmental justice for developing countries with stricter regimes is a crucial asset to the citizens of those countries. A significant provision called public interest litigation (PIL) allowed ordinary citizens to challenge any environmental clearances to projects, policies & actions of the government institutions with minimal effort. This provision exists to date and has played a critical role in Indian judicial history; for instance, Articles 21, 48A, and 51A have expanded the scope of the existing directive principles and interpretation of those articles to include the right to a healthy environment a fundamental right including humans, forests, and wildlife and ensuring the protection through state and penalizing them in case of any violations. However, this still the same template as discussed above (Gill, 2013).

Concerned with the increasing environmental litigations, the recommendations from the National Law Commission and Supreme Court of India, a new court, the National Green Tribunal (hereafter addressed as NGT), solely for the purpose of environmental cases through the NGT ACT in 2010, was established removing the few other less functional tribunal and dispute settlements and joined a small list of countries like Australia, New Zealand. This act provided constitutional validity and autonomy with little to no state influence (Singh, 2021).

III. Significance of the NGT

There are numerous tribunals and dispute settlements within and outside of India. (Pring & Pring, 2016) discusses environmental courts and tribunals (ECTs) in length and breadth and includes a list of active green courts and tribunals globally in the appendix of the publication.

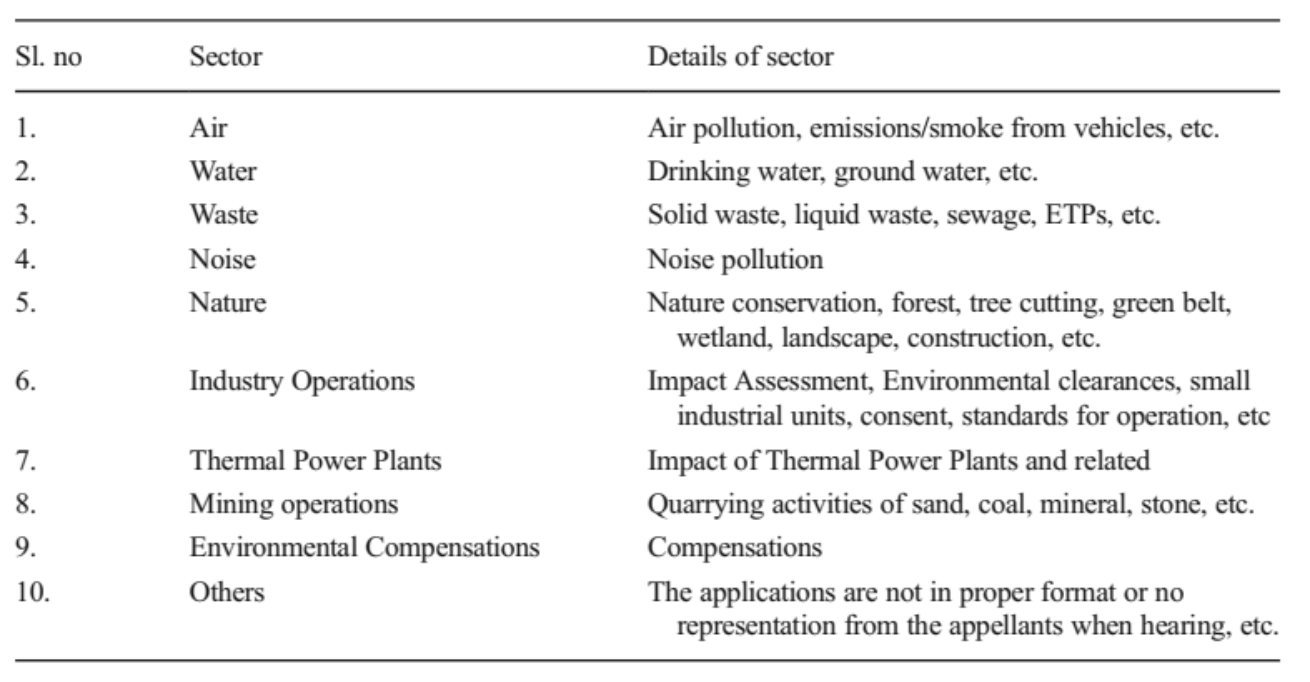

What makes the NGT so special is its people-oriented approach ensuring access to justice as straightforward as possible; for instance, by just sending the court a simple letter regarding a case, the court can start the proceedings, or sometimes, the NGT could also proceed with a case on Suo Moto basis. The NGT's implementation includes seven important laws/acts, which cover water pollution, air pollution, forest conservation, environmental protection, biological diversity, and public liability insurance ( refer to Figure 3 for details on different sectors covered by NGT). Unlike the general courts, which function on civil and criminal codes, NGT judgments are based on the principles of sustainable development, precautionary principle, polluter pays principle, public trust doctrine, and inter-generational equity. The proceedings are in open court, and the judgments are available online (Gill, 2016; Kumar, 2020).

IV. Structure of NGT

The most distinctive feature is that NGT have "green judges" who are independent experts in the field of climate change, forest conservation, water conservation, engineering, and several diverse areas based on requirements (case-by-case basis) with a minimum of 15 years of experts would sit with the traditional judges in case hearings. Independent expert committees are also formed to ensure data-driven and science-based decisions and follow the international environmental principles as indicated above.

The NGT is present regionally and nationally; the Principal Bench of NGT is in New Delhi, with the four Zonal Benches are in Bhopal, Kolkata, Pune, and Chennai. It also follows circuit court procedure regionally, which moves to a different city regionally for a limited period within a year to ensure that access to justice is not restricted due to geographical limitations (Gill, 2016, 2020).

Fig.3. Different sectors covered by NGT (Rengarajan et al., 2018)

Fig.3. Different sectors covered by NGT (Rengarajan et al., 2018)V. Achievements so far

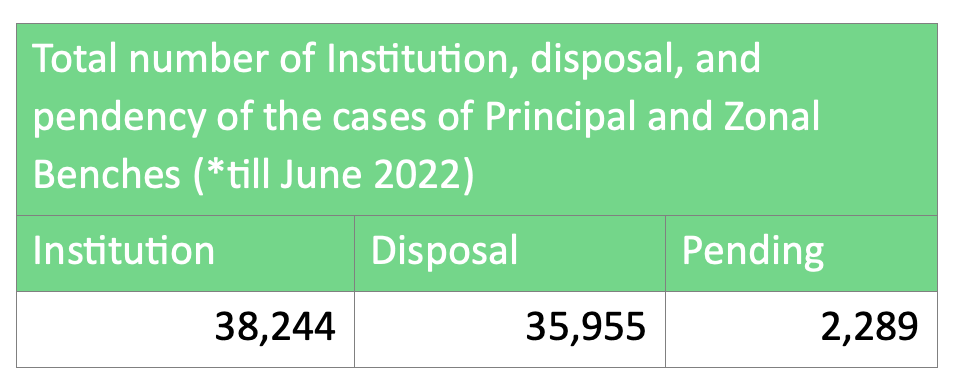

The number of cases listed, disposed of, and pending across all the NGT Benches is shown in Table 1. Now, you might wonder how this is a significant achievement; if we investigate Railway Claims Tribunal, the number of pending cases is 24,133, and in the Armed Forces Tribunal, it is 22,786, and in the traditional courts, the number could shoot up to more than 100,000. Not just the rate of disposal of cases, but if we look into the different sectors, the NGT cases proceed as shown in Figure 3, discussed in (Rengarajan et al., 2018), and the complexity of the proceedings and then completing this within a stipulated period of 6 months per case unless there is a valid reason to extend which the NGT Chairperson needs to agree is nothing short of excellent. The Minister of Law in the national parliament accepted that the disposal rate is greater than the filing rate (PTI, 2022), which is an incredible achievement, especially for developing countries like India.

Table 1. Status of litigation in the five NGT Benches, Source:(National Green Tribunal)

Table 1. Status of litigation in the five NGT Benches, Source:(National Green Tribunal)VI. Personal Impressions and concluding remarks

Considering the limits of our planet to provide us with the resources to sustain our life and our fundamental responsibility to adhere to practical limitations of process and resources is a requirement at this juncture where human activities and social development are exceeding the planetary limits/boundaries and the imminent threat which lies ahead after crossing the boundary cannot be imagined. The stark variations and climate extremes globally in 2022 are just the tip of the iceberg of what lies in the future.

Rights-based litigation, as discussed in the introduction, is considered a strategic tool for litigation, especially in Europe and the USA, which are two models where litigating environmental cases in traditional courts and unique green benches on a case-by-case basis is insufficient to address the complex needs and requirements of doughnut law governance model. Establishing special green courts, like the NGT in India, needs to be implemented globally and within Asia, where the developmental needs should also consider the health of the environment, and the importance of ecological diversity in plant and animal species should be preserved. The NGT uses the established international environmental principles and mandates the participation of expert members along with judges who are experts in civil and criminal law in the judicial proceeding, and is the missing element in rights-based ligation.

References

- Gill, G. (2013). Access to Environmental Justice in India with Special Reference to National Green Tribunal: A Step in the Right Direction. OIDA International Journal of Sustainable Development,, 06, No 4, pp. 25-36. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2372921

- Gill, G. (2016). Environmental Justice in India: The National Green Tribunal and Expert Members. Transnational Environmental Law, 5(1), 175–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102515000278

- Gill, G. (2020). Mapping the Power Struggles of the National Green Tribunal of India: The Rise and Fall? Asian Journal of Law and Society, 7(1), 85–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/als.2018.28

- Jannat, R. (2018). Doughnut Law – Environmental Law for the Anthropocene? The Center for Climate Change, Energy and Environmental Law. CCEEL Blog. https://sites.uef.fi/cceel/doughnut-law-environmental-law-for-the-anthropocene/

- Jasanoff, S., & Nelkin, D. (1981). Science, technology, and the limits of judicial competence. Science (New York, N.Y.), 214(4526), 1211–1215. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.11643671

- Krstinic, D., Bingulac, N., & Dragojlovic, J. (2017). Criminal and civil liability for environmental damage. Ekonomika Poljoprivrede, 64(3), 1161–1176. https://doi.org/10.5937/ekoPolj1703161K

- Kumar, S. (2020). A critical evaluation of national green tribunal of India. International Journal of Law, 6, Issue 06, 1–6. http://www.lawjournals.org/archives/2020/vol6/issue6/6-5-72

- Mahase (2022). Us Supreme Court restricts environment agency's power to regulate carbon emissions. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 378, o1642. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o1642

- National Green Tribunal. https://greentribunal.gov.in/methodology-ngt

- Pring, G. W., & Pring, C. (2016). Environmental courts & tribunals: A guide for policy makers. UN Environment.

- PTI (2022, July 29). NGT's case disposal rate higher than filing rate: Govt. Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/ngts-case-disposal-rate-higher-than-filing-rate-govt/articleshow/93215089.cms

- Rengarajan, S., Palaniyappan, D., Ramachandran, P., & Ramachandran, R. (2018). National Green Tribunal of India-an observation from environmental judgements. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 25(12), 11313–11318.

- Rodríguez Garavito, C. (Ed.). (2021a). Litigating the climate emergency: How human rights, courts, and legal mobilization can bolster climate action (Globalization and human rights). Cambridge University Press.

- Rodríguez-Garavito, C. (2021b). The doughnut approach: how to climatize human rights. OpenGlobalRights. Human Rights at a Crossroads. https://www.openglobalrights.org/the-doughnut-approach-how-to-climatize-human-rights/#:~:text=The

- Singh, a. (2021). A Decade of National Green Tribunal of India: Judgement Analysis and Observations. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-792456/v1 https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-792456/v1